The Use of Fear to Achieve Compliance and the Acceptance of Injustice

Table of Contents

Introduction

Fear-inducing techniques form what appears to be an internationally and historically consistent model: the variations in approach being more a matter of coercive degree rather than formulaic difference. The politics of fear, so far as it relates to the deprivation or diminution of liberty and where it involves a domestic focus, adopts an approach that involves the demonisation of people, usually a small number, by promoting the conclusion that they are a threat to the majority, isolating those who oppose, and gathering support during the process. This process involves the highlighting of difference to obtain the desired result, rather than celebrating a vivre le difference understanding. The isolation of those who oppose the change involves stigmatising and/or inducing the potential opponents to adopt a position that involves concluding ‘the alternative could be worse’.

Reliance is also placed on getting a percentage of potential opponents to support the methods employed through perceived self-interest. The results are always adverse for the individual or minority, even where a majority of people do not fear those being demonised. The consequence can also be adverse for those who allowed the changes to occur. Where the fear is focused on an external source, the model varies to the extent that the larger the perceived threat the better for the authors of fear.

In order for there to be success for the promoters, there needs to be the absence of an independent judiciary, or, instead, a judiciary that does not accept that the liberty of the individual is a fundamental right; or at the very least, a judiciary that will remain mute or accepting during the process of concentrating executive power. The aim of the promoters is to maintain, enhance or achieve power, and in a number of instances, a fringe benefit can be the diversion of the attention of electors from the failures of the government.

The Nature of Fear

The Shorter Oxford Dictionary defines fear as: ‘The painful emotion caused by the sense of impending danger or evil . . . A state of alarm or dread. Apprehension or dread . . . A feeling of mingled dread and reverence towards God or (formerly) any rightful authority . . . A reason for alarm’. This definition suggests that fear is a universally negative attribute, in a cultural sense, it might be considered the opposite of heroism, a trait held in high regard[1].

Beyond cultural considerations though, and far from being a negative character trait, fear has been essential for the survival of individuals within the human race, and by extension, humankind as a species[2]. Looking more broadly still, it is recognised that fear is not restricted to human beings, we are not so special. Fear, or at least the biology of fear, is experienced by virtually all animal species including simple organisms like the Aplysia snail, which has been shown to experience forms of avoidance and anxiety in response to toxic environments[3]. In all cases it serves the same underlying purpose[4]; to protect individuals from danger by starting a process that allows the animal to respond to the stimulus that causes the fear.

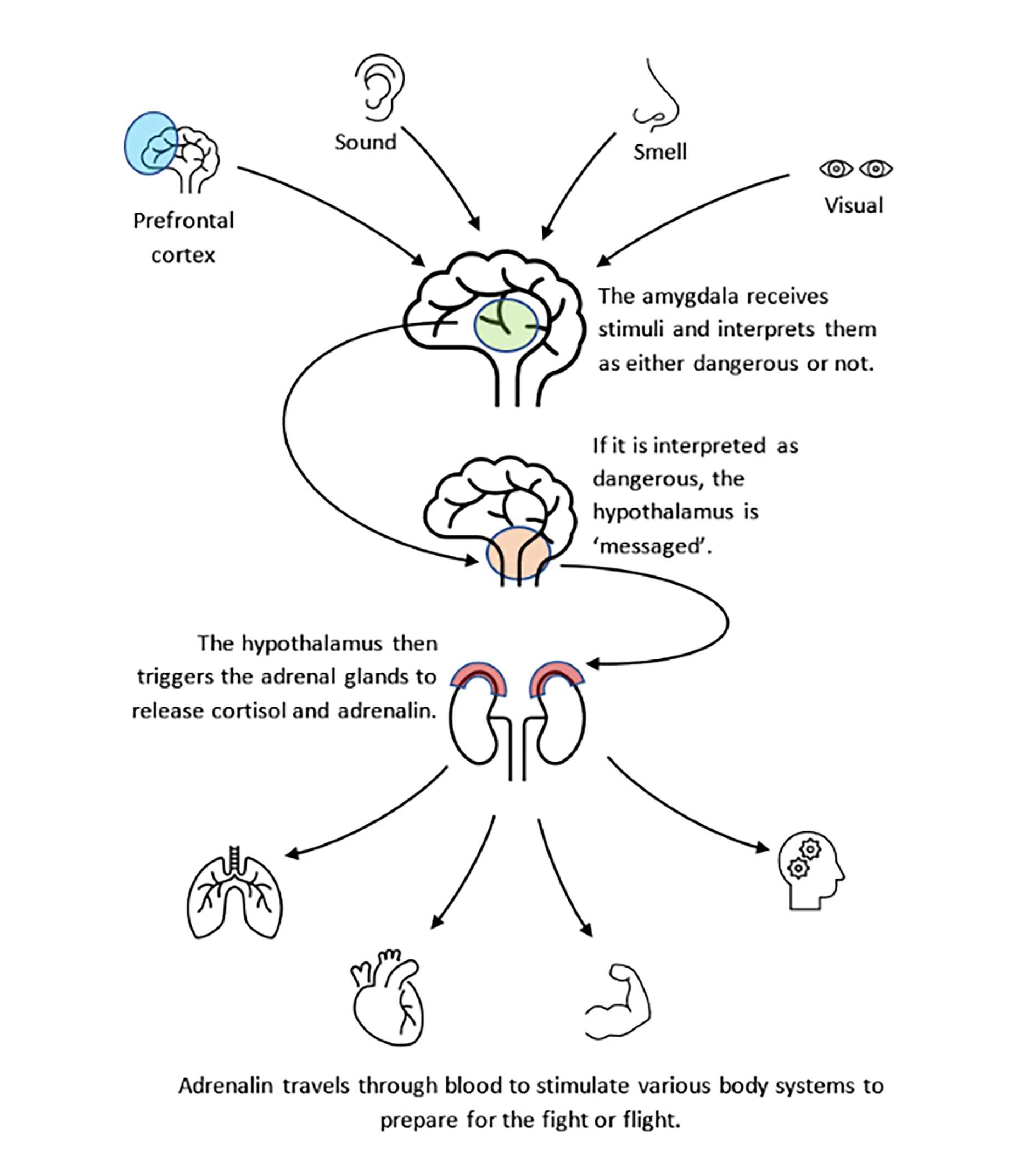

Fear responses related to survival are often referred to as a flight or fight response. This relates to the function of the fear response which is to prepare the individual to run from an imminent danger, or if necessary, to stand and fight to ensure survival. The scientific literature supports the proposition that fear is a physiological response hard wired in our body and incorporates aspects of both our brain and various chemical pathways. The scientific literature points to that part of the brain known as amygdala, as a central part of fear.[5]

The Physiology of Fear

While the neurophysiological underpinnings of fear are only recently being uncovered with detail the earliest research study of the brains of monkeys.[6] How fear is communicated is gradually being understood and involves neurological and chemical communication systems with other parts of the body.

The amygdala is the gatekeeper of the fear response. It receives stimuli from various sources and interprets them as either dangerous or not dangerous. If the amygdala classifies something as dangerous, then long-range neurons[7] running from the central amygdala to other important structures that mediate the fight or flight response.

The Adrenal Response

Adrenalin

Adrenalin is a chemical produced by the adrenal gland and is released when the adrenal receives a signal from the autonomic nervous system, triggered by the hypothalamus in response to different stressors, including fear. Most people are aware of the idea of having ‘an adrenalin rush’ and this can be induced by injecting adrenalin which creates an artificial fear response[8].

When adrenalin is released, it is quickly distributed throughout the body and has an impact on various body systems. These effects are widespread, but all serve to prepare the individual for fight or flight. The changes include:

- Increased heart rate and blood pressure. This may not be noticed by the person, but it can also be experienced as a ‘pounding heart’ and create a sense of discomfort.

- Increase breathing rate. Hyperventilation can create metabolic changes that have a negative effect however provided the person is driven to fight or flight, its value is ensuring that the individual has adequate oxygenation to support the increased activity.

- Increased muscle tension in preparation for activity.

- Dilation of the small blood vessels near the surface of the skin. This causes a flush and often sweating but its purpose I this context is to allow heat exchange to cool the body of an individual who is running or fighting.

- Shutting down activity to the gut and other unnecessary parts of the body saves energy but can also cause nausea and even vomiting in some situations.

- Changing the way we think to create a focus on danger and immediate action and reduce the ability to reason and use broader considerations.

Cortisol

Cortisol is a steroid hormone also produced by the adrenal gland and, in a research paper on ‘Rumination, fear and cortisol’, McCullough et al, demonstrated an increase in cortisol levels where participants ruminated about non-traumatic interpersonal transgressions.[9] The researchers cite other studies showing the relationship between thoughts and a release of cortisol, and that such thoughts do not need to relate to real time incidents in order to induce a cortisol response.

One need not experience such life-threatening stimuli in real time for them to elicit cortisol release: Activating autobiographical memories of such threats is apparently sufficient. Consistent with evidence that mental rehearsal of stressful memories elicits cardiovascular reactivity (Mc Nally et al., 2004; Witvliet, Ludwig, & Vanderhaan, 2001), people with high levels of ruminative thought about life events, including disasters (Aardal-Eriksson, Erikson & Thorell, 2001), motor vehicle accidents (Delahanty, Raimonde, Spoonster, & Cullado, 2003), and sexual abuse (Elzinga, Schmahl, Vermetten, van Dych, & Brenner, 2003), experience increases in cortisol.[10]

Rumination on traumatic events and the production of cortisol can be ‘dynamic and reciprocal rather than unidirectional’.[11] This circularity has the potential, it would seem, to prolong the physiological and therefore the psychological effects.

The adverse consequences of elevated cortisol have been recorded in numerous studies that do not form part of the consideration in this work. Suffice to say that prolonged exposure could not assist with health or with appropriate decision making about events that did not require an immediate flight or fight response. Humans are biologically susceptible to fear situations, and this has the potential to make them vulnerable to fear mongers.[12] The assumption is made that the physiological reaction to politically induced fear would be similar to non-traumatic rumination about interpersonal transgressions.

Fear or Anxiety

Physiologically, fear and anxiety are remarkably similar and use the same pathway starting with the amygdala as the gatekeeper. In fear, there is usually a known and real threat that starts the process, something that almost anyone would consider fearful in most circumstances. For example, standing on a road when a car is about to hit you, or swimming in the water and suddenly noticing a shark fin lurking nearby, are both things that would understandably create a fear response. In these situations, all of the changes discussed earlier in relation to fight or flight, will help to save your life. However, anxiety usually relates to an amorphous stimulus that cannot be identified, it an expectancy of danger rather than actual danger.

The earlier diagram refers to the stimuli from the pre-frontal cortex. Think of this more broadly, simply put as thoughts, and it is clear that it is possible to create the beginnings of a fear response by thinking about something that is anxiety provoking and, if the amygdala interprets it as a danger, then the changes involving the autonomic nervous system, adrenalin and cortisol will be set in motion. This response is usually milder than that required of a fight or flight response though most people experience this as an uncomfortable existence. Nonetheless, a vicious cycle can develop and lead to anxiety severe enough to be described as an illness. This is seen in panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other specific phobias.[13]

Cognitive Responses to Fear and Anxiety

It is clear that fear has been an important survival mechanism for human beings and virtually all other members of the animal kingdom. There can be no doubt that we are hardwired to experience and respond to fear. It is therefore important to understand how fear and anxiety affect our capacity to think, particularly when we consider how both individuals and the population at large can respond to external stimuli that have been presented in such a way that they generate and drive fear.

Self-Preservation

As we have already discussed, fear and anxiety are directed toward self-preservation and this theme becomes a focus of the content of an individual’s thought. Someone experiencing anxiety will tend to become fixated on ideas of preservation. This can involve unreasonable concern about the presence of physical symptoms or illness, but in some situations, it might involve concerns about other people, countries or systems seeking to cause harm.

Distractibility, Lack of Attention & Impaired Cognitive Control

Fear and anxiety lead to an increase in distractibility and concentration impairment.[14] These features are thought to be a product of the development of a bias to detect stimuli and other information related to potential threats.[15]

Coupled with these problems, the ability to undertake more complex cognitive processes, to rationally consider more complex problems, also becomes impaired and less flexible.[16]

Memory Impairment

An extensive body of research has explored memory and the results are complex. However, as before, the results can be understood more easily in terms of the need to focus on self-preservation in the face of potential danger. First, short term memory is impaired, which means people who are fearful or anxious having difficulty remembering what is happening at that time.[17] This is a product of the contemporaneous attentional problems and the excessive focus being given to threat detection rather than laying down memory. Interestingly, anxiety creates a greater deficit for spatial memory than verbal memory but when the individual is exposed to fear caused by shock, both are equally affected.[18]

Executive Functions

Executive functions refer to the combination of the simple cognitive functions, some of which have already been discussed. They include decision making, special navigation and planning. Each of these functions is impaired and a person experiencing anxiety will often comment that they can’t think clearly and describe a sense of being stuck or fixated. This is usually experienced with an increasing sense of frustration and anxiety and sets in train a vicious cycle.

While we are discussing anxiety and fear as the primary emotional drivers, individuals who become immersed in anxiety driven cognitive dysregulation, also begin to experience emotional dysregulation. This leads to the appearance of other emotional problems including depression and sadness, frustration and anger, and overt distress and ‘acopia’.

Anxiety and Fear Creates a Vulnerability

It is clear that human beings are coded and hard wired to detect stimuli that can induce fear and anxiety and to develop a response to it. The impairment of executive function during these periods creates a vulnerability at these times, and this includes the possibility of political manipulation.

Decision Making in the Political Arena

The adverse consequences of prolonged fear-induced stress on physical and mental health are well accepted and documented. The consequences of fear induced decision making in the political arena are not documented in scientific literature.

In the event that an individual is doubtful or confused about whether to support a legislative change, then fear-induced physiological responses probably add to the confusion and allow conditioned biases to enter and make it easier to decide, especially where the people about whom the decision is being made are different. Logically, adopting a biased approach to decision making would not help achieve a fair result.

The assumptions adopted are that there is an emotion called fear, which has a physiological basis and that it can have both positive and negative outcomes. It is also assumed that individuals will respond differently to fear stimuli, and in a small percentage of cases the emotion is not available or is controlled to the extent that it has no influence on decision making. Having adopted the immediately preceding assumptions, this analysis concludes that fear can be a significant influence that clouds political and legal decision making.

History is replete with examples of the promotion of fear to induce certain behaviour. The definition of fear contained in the Shorter Oxford indicates a long-standing promotion of fear in order to obtain religious observance. The bible is full of fearful language and the various institutions promoting religious observance focus on fear to widen their influence. The examination, in this work, of the extent of the use of fear is largely limited to examples relevant to the derogation of fundamental legal rights over the last two centuries.

Theories of the Use of Fear

Thomas Hobbes[19] wrote during the English Civil War of 1642 to 1651 about fear and its role in maintaining the state under the control of the King. He maintained that the terror of death or corporal punishment, if used by the King, played its part in maintaining order, all ultimately for the benefit of the individual and society:

To pray to a King for such things, as hee is able to doe for us, though we prostrate our selves before him, is but Civill Worship; because we acknowledge no other power in him, but humane: But voluntarily to pray unto him for fair weather, or for any thing which God onely can doe for us, is Divine Worship, and Idolatry. On the other side, if a King compell a man to it by the terrour of Death, or other great corporall punishment, it is not Idolatry: For the Worship which the Soveraign commandeth to bee done unto himself by the terrour of his Laws, is not a sign that he that obeyeth him, does inwardly honour him as a God, but that he is desirous to save himselfe from death, or from a miserable life; and that which is not a sign of internall honor, is no Worship; and therefore no Idolatry. Neither can it bee said, that hee that does it, scandalizeth, or layeth any stumbling block before his Brother; because how wise, or learned soever he be that worshippeth in that manner, another man cannot from thence argue, that he approveth it; but that he doth it for fear; and that it is not his act, but the act of the Soveraign.[20]

Corey Robin stresses the anti-revolutionary theme of Hobbes’ work and maintains that fear, as theorized by Hobbes, is promoted as a legitimate adjunct to reason and is ultimately used for ‘preservation and peace’.[21] Robin notes that the frontispiece of the first edition of the Leviathan has an illustration of ‘an apparition king hovering over a walled city. This imposing sovereign keeps watch over the city’s inhabitants and protects them from their enemies’.[22] The concept of fear as a good is designed to use fear ‘to pacify rather than arouse, to instill quiescence rather than awaken hatred’.[23] Robin interprets Hobbes as having a view of fear as being a positive element because people’s view of what is ‘good’ ‘was not shared, self-preservation – and its companions, the fear of death – was no more than a regulative principle among different persons’ irreconcilable conceptions of the good. It was a point of agreement among people who disagreed, requiring of them no substantive, shared, moral foundation, only an acknowledgment of their irresolvable differences’.[24] The justification for inducing fear through threats and then claiming it is necessary for peace is a tactic used over the centuries to pacify those who might object to the punitive activities of governments. It has been most recently used to support the introduction of anti-terrorist and anti-gang legislation. The Hobbesian view is one that seems to reject the notion that people can make agreements and adopt ethical positions without the need for fear to play a role. As a theory it was designed to support the idea that a powerful ruler is required to keep the peace.

Hobbes died in 1679. In 1689 Charles Louis de Secondate, baron de Montesquieu, was born and went on to have a significant impact on the development of the political theory and the role of fear. His approach to the use of fear was markedly different to that of Hobbes and provides a theoretical justification for opposition to tyrannical behaviour and the use of fear to maintain such dominance over society. Montesquieu believed that government power should be limited, and institutions should play a mediating role. Robin contends that there is an agreement between the approaches of both men in that they both suggest fear is a useful tool to gain their vision of the state. He claims:

Like Hobbes, Montesquieu turned to fear as a foundation for politics. Montesquieu was never explicit about this; Hobbesian candor was not his style. But in the same way that fear of the state of nature was supposed to authorize Leviathan, the fear of despotism was meant to authorize Montesquieu’s liberal state. Just as Hobbes depicted fear in the state of nature as a crippling emotion, Montesquieu depicted despotic terror as an all-consuming passion, reducing the individual to the raw apprehension of physical destruction. In both cases, the fear of a more radical, more debilitating form of fear was meant to inspire the individual to submit to a more civilized, protective state.[25]

Alexis-Charles-Henri Clérel de Tocqueville was born on 29 July 1805, fifty years after the death of Montesquieu. He was best known for his works Democracy in America and The Old Regime and the Revolution. Robin credits de Tocqueville with transforming ‘fear’s political meaning and function, signalling a permanent departure from the worlds of Hobbes and Montesquieu. Redefined as anxiety, fear was no longer thought of as a tool of power; instead, it was a permanent psychic state of the mass’.[26] Tocqueville’s view was that democratic nations may stray into despotism but that the consequential degradation would be of a milder form than that experienced before.

Hobbes, Montesquieu and de Tocqueville provide some perspectives on how the use of fear as a controlling force might apply to their societies. In current times, Frank Furedi contends that fear reflects a ‘wider cultural mood’, although it has been ‘consciously politicized’.[27] The purpose of engendering fear in a population ‘is to gain consensus and to forge a measure of unity around an otherwise disconnected elite’.[28] This proposition is perhaps saying no more than fear is used to achieve power over others without the necessity of using brute force or the threat of it. From another perspective it could be said to be a form of consensus building using an emotion to achieve power. The conclusion about the effect of the political use of fear is, as Furedi says, ‘to enforce the idea that there is no alternative’.[29] Discussing alternatives and whether or not change is needed at all is a rational approach. Couching language in terms that provide no alternatives is not productive of rational discussion, especially where it is linked to traumatic events. What it does do is focus attention on the result the promoter of fear wants to achieve and heightens the potential for physiological responses to be engaged in a way that further clouds reason.

The Ultimate Fear

The ultimate fear for most people, it is assumed, is the fear of death. From this ultimate potential outcome, a descending list indicating an order of severity of consequence could be developed. Such a scaled approach, however, could not factor in individual susceptibility to a threat. For example, individuals are affected differently by fear of criticism which could lead to social ostracism. There is no objective measure for the level of anxiety created by the language of fear, or what role fear played in allowing an individual to accept or even promote a change. The ability to determine the extent to which fear motivated the majority of a population to accept change would be even harder to measure. Surveying the population has resource limitations as well as substantial methodological problems that would probably make any attempt of limited worth. What has some value is to examine the extent to which individuals using the language of fear engage in a straightforward manipulation, or if they are also suffering from the effects of fear such that they believe the change is necessary for the good of the community. The distinction is drawn between authors of fear who use the language to maintain or enhance power in a cynical way, and those authors who are using it because they believe they must for the general good. It is assumed that at some point even the most cynical manipulators could suffer anxiety because they fear the loss of power.

If history is any guide an anxious society is likely to question less and be more accepting of authoritarian rule. The greater the anxiety, the easier it is for political leaders to control their populations. The language of fear is also more effective where there is a compliant population that has been conditioned to unquestioningly accept figures of authority. The unquestioning acceptance comes, at least in part, because it is believed that those in authority are more knowledgeable and can be trusted. People tend to be conditioned from childhood not to question authority, and this seems to travel with many into adulthood. A striking example was Malcolm Fraser’s immature acceptance of American assurances that they would be successful in the prosecution of war in Vietnam.[30] The acceptance by the majority of Germans of Hitler’s authority is an example of how a nation can be moved to agree with the persecution and destruction of a minority, and the prosecution of a war.

There are a number of examples in the 21st century of societies where language of fear and the direct application of terror that invokes the ultimate fear of death leads to anxiety that can be seen to paralyse a population and provide a tyrant with absolute power. A good example can be found in North Korea. The best available documentation to support this proposition can be found in the United Nations Human Rights Council Report that details findings of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.[31] The North Korean all powerful, Supreme Leader, and his Party use death, perhaps the ultimate fear, as one method to control its population. The Commission of Inquiry found that all citizens, including children, have witnessed brutal executions. It states:

Almost every citizen of the DPRK has become a witness to an execution, because they are often performed publicly in central places. In many cases, the entire population living in the area where the execution takes place must attend, including children. In other cases, executions are conducted in stadiums or large halls in front of a more selected audience.[32]

The Commission of Inquiry provided many examples of the eyewitness testimony of executions, torture and other fear inducing activities. It also revealed how these methods resulted in unquestioning obedience to the regime. It found no examples of organised political opposition or revolutionary activity. North Korea is perhaps the best 21st century example of how a population can be made subservient to the will of a tyrant, and how fear plays a central role in this successful control strategy. It appears to be a regime exercising absolute control; and unlike other people that have overthrown oppressive regimes, for example, in Timor Leste, there is no organised resistance.

It is axiomatic that the rule of law based on principles of fairness and due process is incompatible with the operation of a totalitarian state where fear is all pervasive and an independent judiciary does not exist. The Commission in its recommendations stressed the need for a fair trial and due process to become part of the North Korean system, as well as the abolition of the death penalty.[33]

The Supreme Leader in North Korea is perhaps carrying to an extreme Hobbes’ theory of the use of fear to control the population. Whether the North Korean leaders actually fear rebellion or invasion, or for that matter whether Hitler or Stalin suffered fear or a serious mental illness is of little moment, because they can be accepted as so perverted as to not warrant concern about whether they genuinely feared an external or domestic threat. It can be accepted that their rigid controls were put in place because they wished to maintain tyrannical power, and the best interests of the populations they controlled were not relevant to them.

It can be reasonably assumed that the North Korean approach to politics does not apply to leading politicians in Australian or other Western democracies. Politicians in democracies are probably deserving of consideration as to whether they actually believed that derogative changes were necessary, to avoid bad consequences for the community. However, the ultimate fear is used by governing bodies in Western democracies when seeking change domestically or for international interventions. It is not usually suggested that if obedience is not forthcoming the state will impose death on its citizen, but rather that if compliance is not forthcoming those who threaten will kill. A good example of this type of fear-inducing manipulation was provided by Liberal member Andrew Nikolic during the short debate on the Counter-Terrorism Legislation (Foreign Fighters) Bill 2014 when he stated: ‘The Prime Minister’s description of Daesh as a ‘death cult’ is most fitting and apt. Such obdurate evil is rare in modern times . . . The Daesh dilemma, and the real danger it poses to humanity, is its ability to harvest, enrage and export malevolence and poisonous disaffection and mayhem, without regard for borders or boundaries. What is certain, however, is that this parasite is hell-bent on killing and barbarity, and this is precisely what this bill is designed to help prevent in Australia.’[34] Using this approach the ultimate fear still has a significant role to play in influencing attitudes towards anti-terrorism legislation.

The Language of Fear

The many forms of the language of fear can include a suggestion that there is some external threat to the country or that there is an internal threat that requires action. Often the promoters of fear will claim that the threat is present both internationally and domestically, thus providing a basis for an all pervasive fear effect. Where the proposed threat is internal, examples of how other counties are dealing with the same type of problem are used. Australia usually follows the United States or the United Kingdom when it engages in the promotion of fear based legal change. Australia has engaged in most of the wars both metaphorical and actual that the United States and the United Kingdom have embarked upon in the 20th and 21st centuries. Where coercion is used to induce fear, it is designed to deter the individual from non-compliance and opposition. This approach fits neatly with legal sentencing principles of specific and general deterrence; but it can be distinguished in that deterrence from performing a criminal act, such as murder, bears little relationship to deterrence designed to stop opposition to a change of law designed to limit freedoms.

Fear of punishment is only one form of coercion; it can take a number of forms. It can also be used to suggest a disloyalty to one’s country, which leads to the opprobrium of the community. There are many examples of this approach, all of them relying on the concept of being sent to Coventry – shunned. This is a simple but effective ploy that may have effect on some people. There are numerous examples, most notably when people are urged to engage in physical warfare. A cultural acknowledgement of the opprobrium that attaches to those who do not want to fight, that has carried relevance for over a century, can be found in the A.E.W. Mason adventure novel The Four Feathers published in 1902. A young male, Faversham, suffers disgrace and receives four white feathers from his friends when he quits the army rather than fighting in the Mahdist War. The feathers symbolised cowardice. Faversham redeemed himself by acts of courage in saving his friends. He also won over his love. The story is simple: either agree, fight and be rewarded, or show cowardice and be shunned.

The language of fear is conveyed in a number of ways: by words that are without ambiguity; by words that are designed to allow an inference to be drawn that is adverse to an individual or group – this can be in the form of dog whistle politics; by actions of the ruling elite that result in damage to their opponents; by penalties imposed; and by the infliction of torture or death. In whatever form it takes, the language is designed to show that there was a threat posed. The induced fear is used to assist with stopping resistance to change, to isolate those who oppose the change, and to garner supporters. If a sufficient reaction can be achieved, the outcome is not one that has been achieved through the process of calm reflection on options available to deal with the perceived threat, or to even consider whether there is a real threat: the more colourful and dehumanizing the language, the greater the result that is being sought to be achieved. An example of such extreme language occurred before the second invasion of Iraq in 2003 when it was claimed that weapons of mass destruction were in abundance and terrorists abounded. Alexander Downer, Minister for Foreign Affairs, was adept in his use of the language of fear, linking the need to invade Iraq with international obligations, weapons of mass destruction and the need to protect Australians from devastating consequences. An example of his rhetoric is when he said in the House of Representatives: ‘Australia will take its place in a coalition to disarm Iraq through military force because we firmly believe we must not resile from our longstanding commitment to rid Iraq of weapons of mass destruction. We should continue to meet our responsibility to . . . enforce disarmament and to protect Australians from a new and potentially devastating threat’.[35] Prime Minister John Howard had promoted a similar line of argument and also raised the potential for the weapons of mass destruction to be obtained by terrorists. He said: ‘As the possession of weapons of mass destruction spreads, so the danger of such weapons coming into the hands of terrorist groups will multiply. That is the ultimate nightmare which the world must take decisive and effective steps to prevent. Possession of chemical, biological or nuclear weapons by terrorists would constitute a direct, undeniable and lethal threat to Australia and its people’.[36]

The fact that the claims about weapons of mass destruction and the potential for them to be obtained by terrorists were not true mattered not at all – the desired result was achieved, without sufficient opposition. The fiction promoted and the result achieved entered, at least for a time, the public arena as truth. Once the falsity of the ‘truth’ is revealed, it becomes largely insignificant because the elite has obtained what it wanted and the public has moved on, becoming diverted with other matters: the lie gets archived.

The language is designed to induce fear in the population in order to bring about change that might otherwise meet overwhelming resistance. It has frequently been successfully employed in Australia and other Western countries. This language is primarily used by politicians and media commentators, but many other players including judicial officers and members of the public join in as the debate intensifies. Results achieved by the use of the fear that are based on lies and that have bad consequences do not result in punishment for the authors of the fear mongering. The commentators continue to exploit fear and the politicians remain in comfort: it is a safe, accepted, and effective method carrying no punitive outcomes for its users. The outcome for those who are the object of the lies can be very severe.[37] Less frequently the threat of coercion designed to induce fear if cooperation is not forthcoming is used during the introduction phase of legislation, in Western countries. For example, when conscription was introduced in Australia during the Vietnam War, the penalty of imprisonment was threatened for conscripts who did not accept that Vietnamese communists needed to be feared or fought by them. In most cases, the desired change is one that carries a punitive element if it is not complied with, once encased in a statute. In the case of anti-terrorism legislation, the penalties for non-compliance are very harsh, even for a person who is not a suspect and refuses to be questioned by the agents of the state. Throughout the process of change, fear is used to initiate, promote, establish and maintain the change.

The language used is designed to elicit the emotion of fear, and it is irrelevant whether the response is flight or fight because the objective has been achieved: the facilitation of a change that may not otherwise be supported. Where it is being used to promote a law that reduces rights, it is usually targeted at a group that does not support the ideology of the government or is culturally different. There are many examples in Australian history where race has been a driving feature. The language does not have to do more than suggest an adverse outcome; it does not have to supply proof that a particular adverse outcome will result if the changes are not adopted. It is often left to the creative abilities of the listener to imagine the consequences. This approach is especially effective if the audience does not have any first-hand experience of the group or individuals being subjected to the laws. Humans, it seems, are very susceptible to fear of the unknown. Racial differences have historically been the easiest to exploit. The yellow peril and the White Australia policy are some of the best-known examples. The violent treatment of Aboriginals, in an extra curial way, in colonial times and the early twentieth century is another example. The white population accepted and promoted the exclusion of Asians, and if they knew about the murder of Aboriginals, most at the very least remained mute in tacit acceptance.

The ease with which a fear can be promoted to the detriment of powerless people is most evident in recent years in the hostility shown by many Australians to refugees. It seems that once fear has been successfully invoked, it is surprisingly easy for those who use it to support specific agendas, to extract from the population the sought-after responses. Some Australians have even adopted the callous view of the fear mongers that people should be placed back on dangerous boats to return to the place from which they came, revealing total indifference to the plight of those people even if some of them are children. Writing in 2001, Peter Mares noted that, whilst the majority of asylum seekers did not arrive by sea, those who did were the object of hostility. His words are still pertinent over a decade later:

There is a contradiction at the heart of Australian society. Like the United States and Canada, Australia is one of the world’s true immigration nations. If we are not Aborigines, then we are migrants, or their recent descendants. Yet, this is a nation hostile to its foundations. For much of our brief history we have been preoccupied with controlling our borders to prevent the entry of others. The White Australia policy is recent, not ancient history; its influence is still felt.[38]

The reason for the hostility remains a fear of those who are perceived to be different. The fear is not rationally based, because Australia is a multicultural nation: but fear is not a rational response to a non-existent danger from boat people. The hostility is fostered and fomented when it suits the political agendas of those inducing fear in the population.

The use of fear has been a historically consistent theme. Perhaps the most striking examples over the past seventy plus years have been the invoking of the communist threat followed, once this threat was no longer available, by the terrorist threat. The attacks in the United States on 11 September 2001 provided fertile ground for the language of fear. This was especially the case in the United States where Tom Pysczczynski suggests that the attacks were the ‘most traumatic events the United States ever experienced’ and that they ‘shook the American people to their core, making them keenly aware of . . . their vulnerability’.[39] This description perhaps cannot be so readily applied to the impact on the Australian population; however, because of the tendency to follow trends in the United States, actual feelings are probably not as relevant.

Even if there is a threat to the community by a group or individuals bent on crime, the language of fear does not require proof that the legislative changes are necessary to deal with that threat. The requirement to show necessity is glossed over to the extent that there is no need to show that a past destructive incident would not have occurred if the law was in place or that the existing laws are insufficient. All that is required is that the words used are sufficiently emotive to give rise to fear that if something is not done bad things will happen. The judiciary is not reticent to engage in use of the language of fear to support otherwise objectionable restrictions on liberty. Callinan J., in Thomas v Mowbray, engages in the process of decision making by reference to events in other countries in a similar, but more constrained way, to that of Menzies. When deciding on the validity of legislation, he introduces events that are largely irrelevant to the matter he needed to consider, but seemingly for him they provided at least some justification for his judgment. The words ring with a justification based on fear:

Judges should keep in mind that distortion, bias, sensationalism, emotion and self-interest are at times common currency in ordinary social intercourse, and in the media. That does not mean that judges should disregard reliable reports and the genuine photographic depiction of, for example, relevantly here, the circumstances preceding, and after, the destruction of the Twin Towers in New York, the bombing of trains in Madrid, and of people and buildings in Bali, and the like.[40]

There was apparently no need to consider whether the laws under consideration would have had any effect on the events outlined, even if they had been in place in the countries where the incidents occurred.

A requirement for the language of fear to be effective is that it identifies a group or individuals as being different. It also needs to be clear that any coercive element will apply only to those who are different and those who oppose. Thus, for example, bikie gang legislation only applies in a punitive sense to those who are gang members and terrorist legislation only applies to terrorists, or those not willing to accept the laws procedural requirements. For members of the public not falling into these categories, comfort can be had that they will not be adversely impacted. This simplistic approach dovetails well with coercion designed to ensure compliance from those who may wish to oppose the legislation but who are fearful of the impact it may have on them.

The following examples of the use of fear to promote political ideology and war span over seventy years. They are chosen to show an approach that remains largely unchanged for current generations of people. The examples are also chosen because they show very clearly the relevance of historical examples and how despite major failures lessons are not learnt; and the leadership of nations continue to re-offend and the majority of the citizen they rule do not attempt to hold them to account.

The Influence of McCarthyism

Senator Joseph R. McCarthy rose to fame in the United States between 1950 and 1954. His surge magnified a threat from the Soviet Union to the United States that, in the words of US Secretary of State Dean Acheson, needed to be presented in terms that were ‘clearer than truth’.[41] McCarthy’s influence commenced on 9 February 1950 when he gave a speech to a small Republican gathering in Wheeling, West Virginia – as part of the unrecorded speech he claimed that there were 205 communists in the State Department.[42] He was a symbol of the times giving his name as a descriptor for the anti-communist activities of the times: McCarthyism.

The 1940s and 1950s in the United States was a period of fanatical anti-communism in which the use of fear was prevalent in order to gain support for legislative change, even when those changes diminished legal rights. The process involved the persecution of members of a minor political party and the isolation and acceptance of this by those who would ordinarily be expected to oppose the attacks on civil liberties. Such monumental change required the acquiescence of the judiciary and the compliance of the community.

Australia has traditionally followed either the United Kingdom or the United States in foreign and related policies. After the Second World War, Australian governments followed with increasing enthusiasm political trends in the United States. Prior to Menzies’ attempts to ban the Communist Party, there were popular anti-Communist activities in the United States. The Alien Registration Act 1940 (Smith Act) was a notable example. It included an anti-sedition section that was authored by Congressman Howard Smith of Virginia.[43] As with Communists in Australia, there was no evidence that any had behaved illegally, yet they were prosecuted and convicted under the law in the United States. Albert Freid notes about the persecution of Communists in the United States and the fact they never behaved illegally:

Whatever one thought of their authoritarian style and modus operandi and their attachment to the Soviet Union, they never behaved illegally until the government decided they did in 1948. By then, moreover, the number of party members was falling rapidly, and so was whatever prestige it still possessed. In any case, the American Communist Party was the smallest and most marginal of any among the world’s democracies. Yet no other democracy prosecuted Communists for being Communists, much less imprisoned them for upwards of five years (some served longer), a miscarriage of justice if ever there was one.[44]

The fear of domestic communism during the 1940s and 1950s did not need to be one held by the majority, let alone based on real concerns, it was sufficient that all potentially effective opposition was muzzled by the fear of being stigmatised as a Communist sympathiser or worse – a Communist. There seems to be an acceptance that over time the public sentiment did grow in favour of the witch hunters. McCarthyism has been frequently compared to the witch trials of earlier centuries. Arthur Miller’s 1953 play The Crucible, a story about the Salem witch trials in Massachusetts in 1692 and 1693, was written as an allegory of McCarthyism. Miller’s penalty for opposing McCarthyism was to be questioned by the House of Representatives’ Committee on Un-American Activities in 1956, where he was asked to inform on Communist writers he knew in 1947. He refused and was convicted by the Federal District Court of ‘contempt of Congress’, but the conviction was overturned in the United States Court of Appeals in 1958. Following his successful appeal, one editorial piece noted:

The real objection to the proceedings taken against Mr Miller was [that] people were required to inform on other people, not because of what they had done but because of what they had been. McCarthyism flouted the principles of Western justice.

Secondly, people were required to inform as a means to their own ritual penance and purification. Congressional committees already knew the names; as in the Inquisition, what was wanted was an “act of faith.”[45]

The growth in criticism of the inquisitional approach did not seem to reduce the anti-communist rhetoric which continued unabated for decades.

Apart from the Smith Act, the Labor Management Relations Act 1947 (Taft-Hartley Act) was also introduced, and it prohibited a number of union activities and notably in terms of anti-communist positioning required union officers to swear affidavits that they were not communists. There soon followed the Subversive Activities Control Act 1950 (McCarran Act) which came into force on 23 September 1950. Apart from requiring Communist organisations to register with the United States Attorney General, it created a Subversive Activities Control Board and contained a provision that allowed the President to apprehend and detain people who may conspire to engage in acts of espionage or sabotage. Its various provisions bear some similarity to the anti-terrorist legislation introduced in Australia over fifty years later.

The liberal communities’ reaction to the rise of McCarthyism is summarised by Fried when he refers to the response of the Civil Liberties Union. Fried notes that ‘liberal groups did not take long to fall in line with the ethos of McCarthyism’ and that the American Civil Liberties Union conducted its own purge of Communists or fellow travelers, the philosopher Corliss Lamont chief among them’.[46]

In Australia the use of the language of fear is clearly shown in the election speech in 1949 of the politician Robert Menzies. He linked a foreign power with Australian communists and stressed the cultural difference between such people and the majority of the population. This group, so he claimed, was so different that they were ‘opponents of religion’. The race difference could not be used because the threat at the time was said to be Russian communism, but religion and law and order were useful invocations that allowed people to use their imaginations to create an outcome that was bad. He stated:

The Communists are the most unscrupulous opponents of religion, of civilised government, of law and order, of national security. Abroad, but for the threat of aggressive Russian Imperialism, there would be real peace today. Communism in Australia is an alien and destructive pest. If elected, we shall outlaw it.[47]

There was no need to provide proof that if the group was not outlawed they would damage the society. For the language of fear to be effective it only requires a belief that some future calamity will occur. Interestingly, despite his vehement rhetoric about the destruction that would be visited upon the community, Menzies not only failed, by 52 thousand votes, to get the Communist Party outlawed, but there was no destruction wrought upon the community by Australian or foreign communists. His failure to provide evidence and accurately foretell the future did not affect Menzies’ popularity sufficiently to cause him to lose an election: possibly it did not affect his popularity at all. He would have to wait until the 1960s before he could introduce racial difference and link it with a communist threat, when he promoted Australia’s disastrous and futile intervention in the Vietnam War.

The Use of Fear in the Vietnam War

An example of the use of an external threat where the application of punishment and shunning was used to obtain compliance was conscription for Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. It involved a continuation of the anti-communist theme. The propaganda framework for the war was established by US President Eisenhower in 1954 when he proposed the domino theory, that was subsequently adopted and used as a justification by Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, and ultimately by Prime Minister Menzies. In a news conference on 7 April 1954, Eisenhower expounded the simplistic domino theory.[48] A year later this image was used by Menzies to justify Australia’s increasing involvement in the Vietnam War. He claimed:

. . . it is our judgment that the decision to commit a battalion in South Vietnam represents the most useful additional contribution which we can make to the defence of the region at this time. The takeover of South Vietnam would be a direct military threat to Australia and all the countries of South and South East Asia. It must be seen as part of a thrust by Communist China between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The task of holding the situation in South Vietnam and restraining the North Vietnamese is formidable.[49]

All the propositions put forward by Menzies as justifications proved to be misleading or simply untrue. Menzies did have form in this regard, his dire warnings about the threat of domestic Communism in the early 1950s were also wrong. Whether he believed his own cant is a moot point, but what is clear is that the level of analysis he applied was simplistic and the language of fear direct and strong. It relied on the long-standing fear of the ‘yellow peril’ to the north, the acceptance of White Australia, anti-Communism, and a desire to follow America. The fact that the approach was bereft of any analysis about what the Vietnamese nationalists actually wanted, or whether there was any real possibility of winning a war for America and its corrupt South Vietnamese government puppets, did not seem to matter to the majority of the Australian electorate or the Australian government. The times were right for the language of fear to be successfully used.

Malcolm Fraser was Minister for the Army from 26 January 1966 to 28 February 1968, and Minister for Defence from 12 November 1969 to 8 March 1971: periods of increasing Australian involvement in Vietnam. His reflections about Australia’s role provide an insight into the decision-making processes involved, and the lies told. Fraser notes that as part of the decision-making process, ‘We accepted too easily that South Vietnam represented something that was good and that Vietminh and North Vietnam represented something that was wrong, very much to be opposed. We cast the issue as a simple case of good and evil when, in reality, it was so much more complicated. If we look at what Australia has done in Iraq and Afghanistan, it is not only America that has failed to learn lessons’.[50] He attempts to justify some of the government’s actions by pointing out that he did not have access to CIA briefings that were not optimistic about success.[51] He even points out that ‘Australian troops were not deployed to Vietnam in response to a request from South Vietnam, [as claimed at the time] but rather as a result of American pressure’.[52] His account shows a government that truly believed they were engaged in fighting evil, and he stresses the integrity of the people involved when he states:

Despite strategic dependence, I still find it impossible to believe that any Australian Government would have taken the course that we did take if they had been fully advised of the assessments McNamara was in fact making and giving to the President. This is regardless of our broader aims at the time of keeping the United States engaged in South-East Asia and adhering to our policy of forward defence and despite our deeply rooted fear of the communist threat. If we had known what the CIA and McNamara both believed at that time – that the cause for which America was fighting in Vietnam was hopeless, and that America and South Vietnam could not succeed – we would never have become so involved. There was information within the US Administration, although the White House was paying no attention to it, that should have been put before an ally.[53]

The claim that the Americans did not allow Australians to have access to views and evidence about the situation in Vietnam is a childlike refrain. His attempt at a justification in hindsight fails to explain why an independent nation did not gather its own evidence and conduct its own analysis of the situation prior to engaging in a process that caused substantial harm and many deaths. There is no reason to doubt that Fraser genuinely recalled events and presented a truthful view. What his recollection and views reveal is that individuals who are affected by fear (in Fraser’s case a belief that good was confronting evil) can fail to make rational and reasonable decisions, and that they can make decisions without necessary proof, even where their actions have internationally adverse consequences.

On 5 November 1964, National Service scheme was announced to assist with increasing the strength of the army and a short time later with fighting in Vietnam.[54] The National Service Act 1964 required 20-year-old males, who were selected by ballot, to serve in the Army for a period of twenty-four months; this was reduced to eighteen months in 1971. After the period of two years’ service a further three years’ service in the Reserve Army was required. In 1965 relevant amendments were made to the Defence Act to allow conscripts to serve overseas. Compliance with the scheme was usual and over 800,000 men registered, 63,000 were conscripted and over 19,000 served in Vietnam. The coercion used to ensure compliance was imprisonment.

Draft evasion grew as the futility of the war became apparent and organisations opposed to it gained increasing publicity. The coercion used to maintain Australian involvement in the war ended with the first decision of the Whitlam government in 1972. Attorney-General, Senator Lionel Murphy recommended to the Governor-General that he exercise his prerogative of mercy and release seven men serving eighteen months gaol. Jenny Hocking notes that following this decision, ‘All pending prosecutions of more than 300 draft resisters would now be dropped and the “lottery of death” that conscription had become would be immediately abolished’.[55] The pain may have ended for those subjected to the draft, but no compensation or apology was given to those in Vietnam who lost their lives or who were maimed. As is often the case, those who engaged the language of fear to allow the destruction went on to live in comfort and prosper; for example, Menzies went into a peaceful retirement, and Malcolm Fraser became Prime Minister.

Fear of Terrorism in Contemporary Australia

The historical landscape had changed by the 2000’s: anti-Communism and the ‘yellow peril’ could no longer be fertile ground for fear mongers. However, the American allies were still present, and the Australian desire to follow remained in place. The new peril of terrorism replaced the communist threat, and the purveyors of fear became active. Race and religion joined the fear rhetoric with Muslims replacing atheists and the yellow peril being replaced by the foreigners from Middle Eastern countries. The role of coercion still played its part for those who did not want to obey the legislative changes. The difference is that there is no ground swell of opposition to the laws, probably because the children of the middle class were not being asked to fight and die, and certainly not being gaoled: there is no need for a ‘Save Our Sons’ movement as in the days of the Vietnam War.

Carmen Lawrence emphasises the need for caution when dealing with the perceived terrorist threat:

The mantra of our times is that the biggest risk to our safety comes from terrorists who might attack us at any moment . . . . In its extreme formulation, this threat is portrayed as evil itself. To the extent that we accept this personification, we are tempted to abandon caution and agree to extreme measures to defeat such an implacable and elusive foe. In all the panic surrounding the rhetoric of the so-called war on terror, little attention has been given to understanding terrorism . . . .[56]

Calls for caution were ignored during the period of the Vietnam War, as were calls for caution before a decision was taken to invade Iraq for a second time. The fear rhetoric, it can reasonably be concluded, was used for cynical purposes. In the United States the linking of terrorism and fear, according to Al Gore, was devised to meet political ends and the fear campaign ‘aimed at invading Iraq was precisely timed for the kick-off of the midterm election campaign in 2002’.[57] He noted in terms of domestic law-making that: ‘The administration also did not hesitate to use fear of terrorism to launch a broadside attack on measures that have been in place for a generation to prevent a repetition of gross abuses of authority by the FBI and the intelligence community that occurred at the height of the cold war’.[58]

The real motivations for those who took the decision to invade Iraq do not actually need to be provided by the critics of the war. It is sufficient to show that the reasons given publicly were lies. It is for the authors of fear to reveal their true motives and for others to determine if their explanations are truthful or not. What can reasonably be excluded as a justification for the invasion of Iraq is that the decision makers actually feared what the Iraqi government could do to cause damage and death in the United States or Australia.

The genuine fear suffered by Fraser, and presumably other members of the government, during the Vietnam War, also appears to be a diagnosis applicable to Liberal Prime Minister, John Howard, when terrorism was introduced as the next major threat to democracies, following the 11 September 2001 attacks in the United States. Howard, if his words are accepted, seems to have had a bona fide belief that there was a need to change the criminal laws in Australia. He was in the United States at the time of the attacks and in his autobiography, Lazarus Rising,[59] he is clear about how he felt: ‘Being in Washington meant that I absorbed, immediately, the shocked disbelief, anger and all of the other emotions experienced by the American people. They were outraged by the audacity and stunned by the chilling effectiveness of the terror mission’.[60] The fear effect was carried with him through the years he was Prime Minister, if the legislative changes are any guide. The depth of his concern is shown in hindsight reflections about feelings during the evening of the attacks:

Janette and I decided to spend the evening at the embassy residence and that afternoon decamped there with a lot of our staff and later had an informal barbecue. We were all still quite numb. It was a sombre occasion and a sad contrast to the spirited optimism felt only two days earlier. It seemed the world had irrevocably changed in 24 hours and that so many things that seemed important just a day or two earlier would no longer be issues troubling us in the months ahead.[61]

Where Robert Menzies had been unsuccessful in promoting legislative change designed to outlaw communists in Australia, John Howard was much more successful with his legislative changes designed to defeat terrorists in Australia. Significantly, there were thousands of communist party members in Australia during Menzies’ time as Prime Minister, but hardly any terrorists for Howard to defeat, if criminal convictions are an indicator. The attempt to derogate fundamental legal rights in the 1950’s and the successful derogation in the 2000’s, were both unnecessary.

The politicians who could normally be expected to oppose changes that derogate fundamental legal rights often resile from taking action or limit their response to trying to make minor amendments to the proposed legislation. Where no real opposition is offered, this can be as a result of a personal visceral fear that involves an unwillingness to oppose because opposition may result in electoral defeat. A striking example of this type of fear involves the Australian Labor Party and its historical attitude to the Communist Dissolution Act. The Labor politicians allowed anti-terrorism laws to go through parliament that included the detention of non-suspects, and the removal of the right to silence and the presumption of innocence, whereas in the 1950s Labor vigorously fought the outlawing of the Communist Party of Australia and laws that would have removed similarly important rights.

Prime Minister John Howard continually used fear to promote legislative changes and Australia’s involvement in wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. An example of his use of the language of fear can be found in an ABC interview in 2005 with reporter Maxine McKew, where he dramatized the terrorist threat to Australia as unprecedented and claimed it would be ‘morally bankrupt’ not to oppose the ‘fanatics’. He stated:

The terrifying thing now is that the weapons available to the fanatics are both more lethal and more easily delivered, and that’s what makes terrorism, modern terrorism, so much more threat threatening.

Maxine, these people are opposed to what we believe in and what we stand for, far more than what we do. If you imagine that you can buy immunity from fanatics by curling yourself in a ball, apologising for the world – to the world – for who you are and what you stand for and what you believe in, not only is that morally bankrupt, but it’s also ineffective. Because fanatics despise a lot of things and the things they despise most is weakness and timidity. There has been plenty of evidence through history that fanatics attack weakness and retreating people even more savagely than they do defiant people.[62]

Krista De Castella, Craig McGarty and Luke Musgrove analysed John Howard’s speeches between September 2001 and November 2007 for their fear arousing content.[63] The analysis was derived from content coded sentences ‘containing core-relational themes of threat or danger, statements which were motivationally relevant, motivationally incongruent, and statements that promoted low or uncertain ability to cope with the present threat’.[64] All but three of the 27 speeches that involved terrorism between 2001 and 2007 revealed the presence of the four key coded components of the fear appraisal.[65] They concluded that ‘the majority of Howard’s political speeches about terrorism met the criteria for promoting fear-consistent appraisals’.[66]

Essentially, John Howard did not have to make public statements about anti-terrorism legislation; his main focus was on supporting the United States in its interventions in other countries. His interest in the rise of the anti-terror laws was perhaps ancillary to his main interest, that of supporting the United States. His rhetoric of fear was stronger in the lead up to the invasion of Iraq in 2003 than it was in 2001. The conclusion I have reached is supported by the analysis of De Castella, McGarty and Musgrove who state: ‘Across other speeches, prevalence of appraisal content varies over time from less than 10% after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, up to approximately 40% just prior to the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. This finding suggests that Howard’s use of potentially fear-invoking language changed over time and context’.[67]

Like Malcolm Fraser, Howard was later to regret his words in the lead up to the invasion of Iraq, once no weapons of mass destruction were found. In an interview in September 2014, he is reported as saying: ‘I was struck by the force of the language used in the American national intelligence assessment late in November 2002. It brought together all the American intelligence and paragraph after paragraph, they said, we judge Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. I felt embarrassed, I did, I couldn’t believe it, because I had genuinely believed it. So, I felt embarrassed, and I did my best to explain … that it wasn’t a deliberate deception. It may have been an erroneous conclusion based on the available information, but it wasn’t made up.’[68]

In November 2007 the federal Liberal government was replaced by a Labor one and there was less emphasis on anti-terrorism laws, although there was no repeal of any of the draconian provisions. In 2013 the Labor government was defeated and a Liberal one led by Tony Abbott came to power. With Abbott’s ascendency new life was given to anti-terrorism laws and ASIO was given significantly more powers. Tony Abbott employed some of the same techniques as John Howard and linked foreign threats to the need for more anti-terrorism laws. In a statement to the House of Representatives on 22 September 2014, Tony Abbott stressed the number of Australians going to fight in Syria and Iraq and linked that to unexceptional and mostly fruitless anti-terrorist raids in Sydney and Brisbane.[69] His aim was to promote further derogating laws and announce the shift of a balance between security and freedom to security. He stated, once again using fear to support his approach:

Regrettably, for some time to come, Australians will have to endure more security than we are used to and more inconvenience than we would like. Regrettably, for some time to come, the delicate balance between freedom and security may have to shift. There may be more restrictions on some so that there can be more protection for others. After all, the most basic freedom of all is the freedom to walk the streets unharmed and to sleep safe in our beds at night.[70]

Again in 2014 an external threat was used to allow for a military intervention in Iraq and Syria, and to allow for the introduction of legislation breaching fundamental legal rights. The Australia Security Intelligence Organisation had raised the official terrorist threat level without providing evidence for the rise or even attempting to justify it. Yet parliamentarians accepted the new level, without questioning the basis on which it had been made. Then Prime Minister Tony Abbott simply stated:

Based on advice from security and intelligence agencies, the Government has raised the National Terrorism Public Alert level from Medium to High.

The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) independently determines the threat level.

The advice is not based on knowledge of a specific attack plan but rather a body of evidence that points to the increased likelihood of a terrorist attack in Australia.[71]

The secrecy and lack of oversight of ASIO does not allow for an independent assessment of the conclusion that the threat level needs to be raised. ASIO does not even allow access to the ‘body of evidence’ upon which it claims it makes an assessment. Furthermore, as noted by John Mueller and Mark Stewart, writing in 2012 about the situation in the United States since 2001, that there has been ‘no terrorist destruction that remotely rivals that inflicted on September 11’.[72] They claim that Americans have been delusional about the extent of any terrorist threat, yet there is no sign of the condition abating with ‘trillions of dollars’ having ‘been expended and tens of thousands of lives . . . snuffed out in distant wars in a frantic, ill-conceived effort to react to an event that, however tragic and dramatic in the first instance, should have been seen, at least after a few years had passed, to be of limited significance’.[73]

There are many examples where fear has been used to introduce anti-terrorism laws. However, there appear to be no instances where it is simply said that the new laws will improve a situation by making the administration of justice fairer for all concerned; or that they will promote the rehabilitation of a group or individuals who are behaving in an aberrant fashion. The need for the change is invariably immersed in simple and frightening language suggesting that, if the change is not made, worse things will happen.

The fear of terrorism was also used to engage Australians in the longest war in its history and that of the United States. In November 2001, Australia joined with the United States and other nations to remove the Taliban from power, defeat al Qaeda and disrupt the use of Afghanistan as a terrorist base of operations. The Taliban reoccupied the capital Kabul on 16 August 2021, and the last US military left Afghanistan on 30 August 2021.

The position of the Australian Prime Minister, John Howard, who committed Australia to the war was:

Australia’s commitment in Afghanistan should continue to receive bipartisan support. The cause is just. It is in this country’s national interest that Afghanistan never again becomes a terrorist haven.[74]

It is reasonable to suggest that the United States and Australia failed to achieve the objectives said to provide the basis for the invasion.

What is underemphasised is that engaging in warfare involves the massacre of the innocent. The war on terror has killed a lot of people who had done nothing to harm the interests of Australia or the United States. Those who started the invasions that resulted in the massacres have not suffered any penalties. The statistics below come from the Watson Institute, Brown University[75]and they provide some data, albeit understated, of the numbers killed over a twenty year period.

Human Cost of Post-9/11 Wars: Direct War Deaths In Major War Zones, Afghanistan & Pakistan (Oct. 2001 – Aug. 2021); Iraq (March2003 – Aug 2021); Syria(Sept. 2014 – May 2021); Yemen (Oct. 2002-Aug. 2021) & Others Post-9/11 War Zones

The number of people killed directly in the violence of the U.S. post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere are estimated here. Several times as many more have been killed as a reverberating effect of the wars — because, for example, of water loss, sewage and other infrastructural issues, and war-related disease. Posted September 1, 2021.

Afghanistan | Pakistan | Iraq | Syria/ISIS | Yemen | Others | TOTAL | |

U.S. Military | 2,324 | – | 4,598 | – | – | 130 | 7,052 |

U.S. DoD Civilian | 6 | – | 15 |

| – | – | 21 |

U.S. Contractors | 3,917 | 90 | 3,650 | 19 | 2 | 511 | 8,189 |

National Military & Police | 69,095 | 9,431 | 45,519-48,719 | 80,600 | – | N/A | 204,645-207,845 |

Other Allied Troops | 1,144 | – | 323 | 13,407 | – | 14,874 | |

Civilians | 46,319 | 24,099 | 185,831-208,964 | 95,000 | 12,690 | N/A | 363,939-387,072 |

Opposition Fighters | 52,893 | 32,838 | 34,806-39,881 | 77,000 | 99,321 | N/A | 296,858-301,933 |

Journalists/Media Workers | 74 | 87 | 282 | 75 | 33 | 129 | 680 |

Humanitarian/NGO Workers | 446 | 105 | 63 | 224 | 46 | 8 | 892 |

TOTAL (to nearest 1,000) | 176,000 | 67,000 | 275,000-306,000 | 266,000 | 112,000 | 1,000 | 897,000-929,000 |

This chart tallies reported deaths caused by direct war violence. It does not include indirect deaths, namely those caused by loss of access to food, water, and/or infrastructure, war-related disease, etc. The numbers included here are approximations based on the reporting of several original data sources. Not all original data sources are updated through mid-August 2021; dates are noted in the footnotes. The allocation of deaths into categories is often disputed because actors disagree on whether a person killed was a combatant or non-combatant. Sources tend to be conservative, only counting deaths which researchers have verified through two or more independent sources. As noted below, there are not consistent reports or estimates for most of the deaths in the smaller war zones in the Other category.

Donald J Trump provides another example of a fear mongering leader of a nation. One of his most disruptive tactics was to claim that he did not lose the presidential election. He used the language of fear to try and overturn the election. On 6 January 2021 in Washington in a long ranting speech to his followers, during which members of the crowd shouted, ‘We love you’, he said, inter alia:

All of us here today do not want to see our election victory stolen by emboldened radical-left Democrats, which is what they’re doing. And stolen by the fake news media. That’s what they’ve done and what they’re doing. We will never give up, we will never concede. It doesn’t happen. You don’t concede when there’s theft involved.

. . . .

But this year, using the pretext of the China virus and the scam of mail-in ballots, Democrats attempted the most brazen and outrageous election theft and there’s never been anything like this. So pure theft in American history. Everybody knows it.

. . . .

They also want to indoctrinate your children in school by teaching them things that aren’t so. They want to indoctrinate your children. It’s all part of the comprehensive assault on our democracy, and the American people are finally standing up and saying no. This crowd is, again, a testament to it.

. . . .

Together, we will drain the Washington swamp and we will clean up the corruption in our nation’s capital. We have done a big job on it, but you think it’s easy. It’s a dirty business. It’s a dirty business. You have a lot of bad people out there.

. . . .

And we fight. We fight like hell. And if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.

. . . .

So we’re going to, we’re going to walk down Pennsylvania Avenue. I love Pennsylvania Avenue. And we’re going to the Capitol, and we’re going to try and give.[76]

The crowd moved and invaded their parliament. His right wing supporters had been roused to act on lies.

Using Fear is Deliberate, or Is It?

We have been discussing the idea that inducing fear in others can be a tool to attain certain goals. There are countless historical examples to suggest that this is a deliberate ploy leaders use to control the people they lead, in effect to ensure submission to their own will. However, it is worth considering whether this is a deliberate effort, or a natural tendency.

Using Fear to Control is a Common

In truth, virtually everyone uses fear to obtain compliance in others. Perhaps the best example of this is the way parents control the behaviour their children with the use of fear. Parents of young children often use fear of a consequence to obtain a behavioural outcome for their children. Variations of “If you do X, Y will happen, and your life will be ruined” are commonplace and they can be effective in preventing X by threatening Y.

The various religions have also tended to use fear to induce a particular type of behaviour, or perhaps discourage certain types of behaviour. The Ten Commandments imply that if you commit one of the ten sins, hell awaits. If you are fearful of hell, then it serves as a strong discouragement of that behaviour. The expression ‘Fear of God’ can be found in some form of a number of religions with numerous references. For example, in Christianity in Luke 1:50, Mary says, “his mercy is from age to age to those who fear him.”, in Islam. The term Taqwa means “piety, fear of God”[77]; in Judaism, Isaiah 11:1-3, the prophet says: “The spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him: a spirit of wisdom and of understanding, A spirit of counsel and of strength, a spirit of knowledge and of fear of the Lord, and his delight shall be the fear of the Lord.” And in Proverbs 9:10, fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.”

This indoctrination process is continued in school where children again are ‘victims’ of using fear to control their behaviour. Again, as parents have done, the school system including teachers use fear to ensure their students behave in a way that fits in with their own needs.

The indoctrination of young people developing in society repeatedly uses fear as a mechanism to control. Often this fear is induced by people who are themselves afraid. Parents who are afraid their children will be injured on the road by not being careful, will use fear to obtain compliance. Stranger danger programs designed to ensure children are suspicious of people they don’t know is an attempt to use fear to prevent children from becoming victims of child abduction.

From our earliest experiences, people are taught to respond to fear presented by those in authority from our earliest experiences. So when, as adults, political leaders seek to control the populations with fear. For some leaders, it is likely that just like the parents, their use of fear to control is instinctive and may even be a product of their own fear. Examples of this type of control have potentially been evident in the COVID pandemic in Australia. Repeated restrictions on day-to-day life have been invoked and for most part, the population accepted it. However, this control was most likely driven by fear in the leadership. Fear that many people would die, fear that they would be blamed for the deaths, and fear that they might be responsible for deaths. The leaders demonstrated a low level of risk tolerance.