Growth of Restrictions on Fundamental Legal Rights since 2001

Table of Contents

The main examples of legislation used to show the restriction of rights are drawn from the Commonwealth Criminal Code 1995, the Crimes Act 1914, and the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004. The examples show a paradigm shift of Australian government acceptance of the protection of fundamental legal rights as an integral part of the laws, to a rapid and exponential growth in criminal laws that specifically exclude those rights.

The growth in anti-terrorism legislation in Australia has been continuous since 2001. In 2015 Lynch, McGarrity and Williams identified 64 separate pieces of legislation.[1] With the passage of the Metadata laws in 2015 the number of laws is at least 65 and growing. In order to understand the way the laws breach fundamental legal rights, it is necessary to appreciate in detail two critical implications of these laws taken as a whole. First, how they have broken the interdependent relationship between the various arms of the criminal justice system. Second, the degree of shift from pre-2001 restrictions on fundamental legal rights and the non-existent nature of any monitoring of the implications of the shift. To demonstrate these implications an extensive and detailed analysis of the legislation is required. This analysis will show that what has occurred is the creation of a parallel criminal justice system that deviates dramatically from the traditional criminal justice system.

Anti-terrorism Laws and the Criminal Code

Definition of Terrorism

A significant number of the anti-terrorist laws are contained in the Criminal Code Act 1995, at Schedule 1, Part 5.3. The definition of a terrorism offence is found in the Criminal Code 1995 and it was introduced through the Security Legislation Amendment (Terrorism) Act 2002 which also introduced a number of terrorism related offences.[2] Division 100, Part 5.3 of the Criminal Code Act 1995 governs terrorism offences. Section 100.1 defines a ‘terrorist act’ as: ‘(b) the action is done or the threat is made with the intention of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause; and (c) the action is done or the threat is made with the intention of: (i) coercing, or influencing by intimidation, the government of the Commonwealth or a State, Territory or foreign country, or of part of a State, Territory or foreign country; or (ii) intimidating the public or a section of the public.’ Subsection (2) further qualifies the definition requiring a terrorist act to have one or more of the following components: ‘(a) causes serious harm that is physical harm to a person; or (b) causes serious damage to property; or (c) causes a person’s death; or (d) endangers a person’s life, other than the life of the person taking the action; or (e) creates a serious risk to the health or safety of the public or a section of the public; or (f) seriously interferes with, seriously disrupts, or destroys, an electronic system including, but not limited to: (i) an information system; or (ii) a telecommunications system; or (iii) a financial system; or (iv) a system used for the delivery of essential government services; or (v) a system used for, or by, an essential public utility; or (vi) a system used for, or by, a transport system’. In case there is any doubt because the qualified definition provides for a physical action on the part of an offender for a terrorist offence to have been committed, section 80.2C deals with advocating terrorism and subsection (4) states: ‘A reference in this section to advocating the doing of a terrorist act or the commission of a terrorism offence includes a reference to: (a) advocating the doing of a terrorist act or the commission of a terrorism offence, even if a terrorist act or terrorism offence does not occur; and (b) advocating the doing of a specific terrorist act or the commission of a specific terrorism offence; and (c) advocating the doing of more than one terrorist act or the commission of more than one terrorism offence’. Additionally, Division 101, examined below, allows for planning a terrorist act, training for such an act and possession or collection of things to facilitate a terrorist act to also be criminal, although no act causing injury or death is necessary. The Crimes Act 1914 and the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979 provide definitions that refer to the Criminal Code and provide no better definition of what a terrorist offence involves than outlined.

One of the most significant requirements to meet the definition of a ‘terrorist act’ is that the motivation for the crime be ‘done or the threat is made with the intention of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause’. This requirement provides an element to the offence that is rarely found in other criminal laws. [3] For example, if subsection ‘(c) causes a person’s death’ is involved and traditional criminal laws applied then absent justifiable homicide, the criminal charges of murder or manslaughter could be laid and motive is not an element of these offences. It may be that motive is essential if there is to be a separate group of substantive crimes applicable to terrorists, otherwise the terrorists just join a queue with other alleged offenders who are charged with serious indictable crimes. This proposition leaves open the possibility that many of the laws were just politically inspired vote harvesting.

Difficulties Applying Definition of Terrorism

Where there is an individual offender not connected with any group espousing a political, religious or ideological cause, the Criminal Code does not preclude the person being charged with a terrorism offence. The use of the anti-terrorism laws contained in the Criminal Code where other criminal laws that contain due process legal protections for an accused are available raises the real prospect of the laws being used for political gain, or for the convenience of enforcement agencies who do not want to be restricted in the investigative stage by a suspect claiming a right to silence or requiring a lawyer. The difficulty could also arise, for example, where a person intends to steal for personal financial gain but through words falsely links their actions to a political, religious or ideological cause; or commits the crime because he or she is mentally ill and claims one of the motives required for a terrorist act. The possibilities are numerous.

The difficulties with applying the section are highlighted in section 100.1(3) which excludes action from the terrorist frame, if they involve: ‘advocacy, protest, dissent or industrial action’; and they are not intended: ‘(i) to cause serious harm that is physical harm to a person; or (ii) to cause a person’s death; or (iii) to endanger the life of a person, other than the person taking the action; or (iv) to create a serious risk to the health or safety of the public or a section of the public’. By including this exception some of those in parliament must have been aware that the very broad definition given to terrorism offences could well include industrial action. Indeed, it still does if there is intention to cause one of the harms listed.

A problem arises with the attribution of intention, especially where there is disagreement about the creation of serious risk to the health or safety of the public or a section of the public. The protests about mandatory vaccination and lockdowns because of the coronavirus have the potential to be called acts of terrorism. Additionally, a problem greater than the attribution of specific motives to the crimes concerns the procedures that have been introduced to deal with the motive based criminality: procedures that can be easily abused, that remove fundamental legal rights, and that are covered in a cloak of secrecy. The scope is present in the Criminal Code and the other legislation to allow political opponents to be scandalised and oppressed; and the powers are so broad that an anti-democratic elite could engage in active suppression of public dissent. This could not have as easily been achieved before the introduction of the anti-terrorism amendments to a number of Acts in the 21st Century.

Preparing or Planning a Terrorist Act

Division 101 contains a number of sections specifying particular offences and penalties.[4] Section 101.1(1) allows for life imprisonment for a terrorist act; section 101.2 provides 25 years imprisonment for providing or receiving training connected with a terrorist act; section 101.4 has 15 years imprisonment for possessing things connected with terrorist acts; section 101.5 allows for 15 years imprisonment for collecting or making documents likely to facilitate terrorist acts; and section 101.6 has a penalty of life imprisonment for acts done in preparation for, or planning of terrorist acts. Section 101.6 is extremely broad, creating an offence if a ‘person does any act in preparation for, or planning, a terrorist act’, and it does not matter if ‘a terrorist act does not occur’, or if there was a ‘specific terrorist act’ contemplated, or if the was going to be ‘more than one terrorist act’.

Intention to commit a terrorist offence is required for the offence to be committed. The intention can be inferred from words said or actions. For example, a discussion with another person may be sufficient. However, the act done can be as a simple as downloading plans for bomb making from the internet, if there is some evidence that there was planning to carry out a terrorist act. The planning could, for example, be inferred from the discussion with another person which can also be used to show intention. The possibilities are open ended and can be inferred from a series of actions or words which by themselves are innocuous. It does not matter if the plans were unlikely to be successful or in fact did not eventuate. The planning can, for example, be an adolescent fantasy that goes nowhere, but the person can still be sentenced to life in prison if they engage in the planning process and the requisite intention is proved. In the case of Regina v Lodhi [5], where the prosecution used section 101.6, to bring its case that planning occurred to bomb part of the electricity supply system, Whealy J stressed in his sentencing remarks, the potential for serious consequences from planning, and found an analogy in an event that had nothing to do with terrorism but that he thought had ‘consequences on the national psyche’ in the ‘tragedy’ of the Port Arthur massacre, ‘to realise how a major terrorist bombing would or could impact on the security, the stability and well-being of the citizens of this country’.[6] He placed emphasis on the potential rather than an actual adverse outcome of the planning, stating:

It may well be that there was a general lack of viability and sophistication about his actions. It may well be that there was a degree of impracticability as to whether he would be able to carry out his criminal intentions. On the other hand, even the most amateurish and ill-conceived plot to cause mayhem by the use of explosions would be capable of causing considerable damage and even death amongst our community.[7]

Prior to the verdict of guilty and the imposition of sentence, an appeal was lodged on the grounds that: retrospective amendments did not to apply to a trial that had commenced; the amendments violated the Commonwealth Constitution; the Crown failed to specify the terrorist acts for which preparation was being made; the counts in the indictment were duplicitous; and the indictment did not contain the essential elements of the offence.[8] The New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal with Spigelman CJ, McClellan CJ at CL and Sully J agreeing held that: retrospective amendments did not apply to a case that had commenced and therefore it was not necessary to consider Constitutional issues;[9] the parliament had decided to create an offence where it was not necessary to specify precisely what an accused intended to do;[10] the parliament intended to create an offence with one or more characteristics;[11] and the essential elements of the offence had to be specified.[12] The case was sent back to the trial judge.

As part of the consideration of the grounds of the appeal Spigelman CJ pointed out the unique nature of the legislation and that the courts need to respect the policy decisions of parliament. He stated:

Preparatory acts are not often made into criminal offences. The particular nature of terrorism has resulted in a special, and in many ways unique, legislative regime. It was, in my opinion, the clear intention of Parliament to create offences where an offender has not decided precisely what he or she intends to do. A policy judgment has been made that the prevention of terrorism requires criminal responsibility to arise at an earlier stage than is usually the case for other kinds of criminal conduct, e.g. well before an agreement has been reached for a conspiracy charge. The courts must respect that legislative policy.[13]

The court concluded that the parliament had decided to allow for duplicitous offences, and to remove the requirement that the prosecution specify what a person charged under the section intended to do. The preparation or planning offence allowed for in section 101.6 has extraordinary reach. Arguably, it goes beyond attempt to commit a crime. It also goes beyond the inchoate offences of conspiracy and incitement which require a minimum of two people. A person, for example, who purchases a balaclava to be used to enter a bank and disable its computer system, because the bank is part of the capitalist system which he or she ideologically opposes, could be found guilty of preparing for a terrorist act. This would be the case even if the person could not possibly gain access to the computers because they were computer illiterate, and did not know where the computer system was located. The law allows for the stupid and vulnerable to be caught but probably would be ineffective against an Al Qaeda member. In the event that section 101.6 was amended to remove the requirement for motive to be an element there could be a vast increase in the number of offenders. This, no doubt, would require substantially increased funding to the criminal justice system, assuming that the police bothered trying to enforce the law. This section is a very clear example of a parallel legal system.

Proscribing Terrorist Organisations

Division 102, section 102.1 contains the definition of a terrorist organisation. It has a general definition in subsection (a) ‘an organisation that is directly engaged in, preparing, planning, assisting in or fostering the doing of a terrorist act’. Subsection (2) (b) allows for such organisations to be listed in regulations. The section gives the Minister the power to list organisations if satisfied on reasonable grounds that the organisation ‘(a) is directly or indirectly engaged in, preparing, planning, assisting in or fostering the doing of a terrorist act; or (b) advocates the doing of a terrorist act’. Subsequent sections make members of such an organisation criminals who can suffer substantial periods of time in gaol. The definition would allow the use of literature produced by an organisation to be used as evidence that it was a terrorist organisation: there is no requirement that the organisation has actually been involved in terrorist activities.

The initial listing seems to be at the discretion of the Australia Federal Police Minister, but pursuant to section 102.1A it can be reviewed by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security and it is possible for a House of Parliament to disallow the regulation within 15 sitting days’ time after the regulation has been laid before the House: subsection (3).[14] The likelihood of parliamentarians disallowing a regulation listing a terrorist organisation is not known; but if any guidance can be taken from the eagerness with which both Labor and Liberal governments have embraced anti-terrorist legislation, no reliance could be placed on gaining support for a disallowance. The fear of opposing the listing of an organisation would be present for those parliamentarians who want to avoid being labeled as soft on terrorism.

Difficulties Applying Proscribing Terrorist Organisations Laws

The process for proscribing an organisation does not allow any member of the organisation to the opportunity to be heard prior to the organisation being listed. This is a denial of natural justice which usually forms part of due process rights in all courts and tribunals to assist in ensuring fairness.[15]

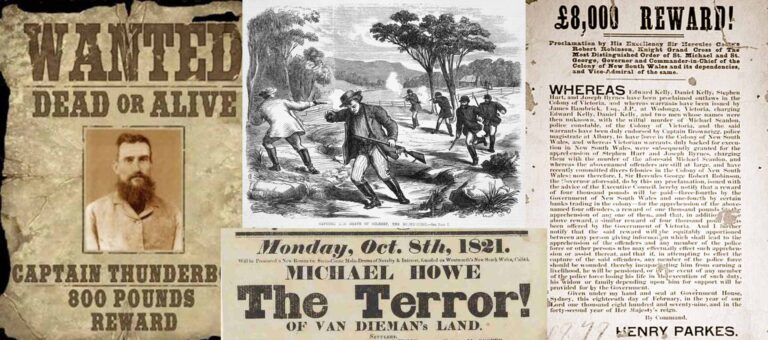

An additional problem exists in that any member of a listed organisation who wanted to advocate for the removal of the organisation from the list would be exposing himself or herself to prosecution for being a member. Furthermore, section 102.8 may make it very difficult for anyone to advocate for the removal of an organisation from the list, if it was open to argue that the person had an association with the organisation: 3 years goal being the penalty for association. The section is designed to stifle the freedom of association, and dissent about government decrees. Regulation making power of this kind would no doubt have been appreciated by Prime Minister Robert Menzies, who may well have been successful in banning the Communist Party of Australia if terrorist powers of the kind found in the Criminal Code had existed in the 1950s. The Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950 was passed on 19 October 1950 and received the Governor-General’s assent the next day. It contained nine recitals six of which referred to the Australian Communist Party. The fourth recital claimed, ‘the Australian Communist Party, in accordance with the basic theory of communism, as expounded by Marx and Lenin, engages in activities or operations designed to assist or accelerate the coming of a revolutionary situation, in which the Australian Communist Party, acting as a revolutionary minority, would be able to seize power and establish a dictatorship of the proletariat’. The fifth recital contended that ‘the Australian Communist Party also engages in activities or operations designed to bring about the overthrow or dislocation of the established system of government of Australia and the attainment of economic, industrial or political ends by force, violence, intimidation or fraudulent practices’. If the High Court had not acted to disallow the legislation many people who were of good fame and character and who served their country in wars and in many positive ways would have been branded terrorists.

The laws proscribing organisations have not been supported by any evidence as to their effectiveness. As noted by Roger Douglas:

There is pitifully little evidence bearing on the impact of proscription laws on group and individual behaviour. We have little idea of who refrains from what and to what extent this is a result of proscription laws. We do not know whether and to what extent laws which proscribe particular groups incite those who vaguely sympathise with such groups to provide more support than they otherwise would. Nor do we know how far plotting on behalf of terrorist groups is a substitute for, rather than a precursor to, action.[16]

Section 102.1 also includes a definition for ‘advocates’ that provides at section 102.1(1A)(c) the following: ‘the organisation directly praises the doing of a terrorist act in circumstances where there is a substantial risk that such praise might have the effect of leading a person (regardless of his or her age or any mental impairment that the person might suffer) to engage in a terrorist act’. If the section had existed when the African National Congress was fighting for liberation from the apartheid regime then praise of Nelson Mandela could have led to imprisonment. Currently, praising the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) could be regarded as a terrorist offence despite the fact that it is fighting the Islamic State. Apart from the potential impact on individual liberty, the section impacts on the constitutional right to communicate about political matters.

Division 102, Subdivision B creates a series of offences relevant to an organisation caught by section 102.1(a) or by regulation pursuant to subsection (b). Section 102.2(1) provides 25 years imprisonment for intentionally directing the activities of a terrorist organisation, and subsection (b) 15 years imprisonment for recklessly directing the activities of a terrorist organisation. Section 102.3 creates a 10 year imprisonment penalty for being a member of a terrorist organisation, subsection (2) provides a defence if the person can prove that he or she took reasonable steps to cease being a member. The defence is one of the many that reverses the onus of proof in such legislation: the emphasis is on freeing the State from the need to prove its case beyond reasonable doubt where a defence is raised. For example, if self defence is raised in a trial it is for the prosecution to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the defence was not available in the circumstances of the case.

Section 102.4(1) has a 25 years imprisonment penalty for intentionally recruiting a person to be a member of a terrorist organisation, and subsection (2) allows for 15 years for recklessly recruiting. Section 102.5 allows 25 years imprisonment for providing training to a terrorist organisation, receiving training from such an organisation and intentionally participating in training. Section 102.6 has penalties of 25 years imprisonment for intentionally receiving or collecting funds, and 15 years for recklessly so doing. Section 102.7 makes it an offence to intentionally or recklessly support a terrorist organisation, with penalties of 25 years and 15 years respectively. Section 102.8 provides a 3 year penalty for associating with a terrorist organisation. It is a strict liability offence to intentionally associate knowing the organisation is a terrorist organisation or that it is listed in the regulations. Subsection (4) allows some exceptions including if the association is for the purpose of providing legal advice on a limited range of matters. As is usual with such sections, the burden of proof rests with the defendant to show an approved association. The effectiveness of such legislation in dealing with political, religious, or ideologically based criminal activity remains to be seen. However, as a matter of common sense, it is unlikely to deter hard core terrorists, as banning and punitive laws failed to defeat revolutionary efforts over the centuries. The most it can reasonably be expected to achieve is to deter people who might only flirt with such organisations, or inspire stupid and disaffected youth to engage with such organisations. A consequence that would be detrimental is where an organisation is banned that is simply trying to achieve freedom from a tyrannical regime.

The Law Council of Australia has recommended the repeal of section102.1(1) and the introduction of a fairer, transparent system that includes the requirement that the Minister apply to the Federal Court for an organisation to be listed and that the application be held in open court. Additionally, it recommended that there be stated criteria for proscription, detailed procedures for revocation and wide publicity if an organisation is proscribed.[17]

Division 103, section 103.1 provides for life imprisonment for providing or collecting funds and the person is reckless as to whether the funds will be used to assist or engage in a terrorist act. It does not matter if the act actually occurs, or if it involves a specific terrorist act or more than one for the offence to have been committed. Section 103.2 provides for life imprisonment where a person intentionally, directly or indirectly makes funds available or collects funds available to assist or engage in a terrorist act. As is the case with section 103.1, it does not matter if the terrorist act occurred or whether there were one or more acts.

Control Orders

Control orders were introduced with the Anti-Terrorism Act (No. 2) 2005 and are clearly contentious in that they place fetters on the liberties that are normally enjoyed by people in Australia who are not charged with a criminal offence.[18] They also substantially change normal prosecution criminal disclosure requirements, shift the onus of proof, alter court procedures that are normally required for an accused to have a fair trial, restrict communication and contain significant penal provisions for non-observance of restrictions. An order can be placed on an individual even if they will never face a criminal charge. It can also be placed before or after a person has served a sentence of imprisonment, or even if the person is found not guilty following that verdict or at the same time. Only a selection of the sections is detailed and analysed: they have been chosen on the basis that they best illustrate what a control order is and how it restricts fundamental legal rights. Control orders are a good illustration of how the parallel criminal justice system significantly varies from the traditional system.

The Anti-Terrorism Act (No.2) 2005 introduced control orders, which became part of the Commonwealth Criminal Code Act 1995 (Division 104). Following additional amendments, the object of the Division is described in section 104.1: ‘to allow obligations, prohibitions and restrictions to be imposed on a person by a control order for one or more of the following purposes:

- protecting the public from a terrorist act;

- preventing the provision of support for or the facilitation of a terrorist act;

- preventing the provision of support for or the facilitation of the engagement in a hostile activity in a foreign country.’

The order is therefore for the purpose of dealing with an unspecified future threat. The proper desire to protect the public from a terrorist act cannot in itself be criticised. The problem is that in trying to protect, provisions have been placed in the Criminal Code that allow significant breaches of fundamental legal rights: in the case of control orders this is done without any evidence that a law of the same type has prevented any terrorist attack in any part of the world. The law is thus a predictive tool whose utility is unknown.

Control Orders Police and Ministerial Power

Section 104.2 allows an Australian Federal Police (AFP) member to seek an interim control order with or in ‘urgent’ circumstances without the consent of the AFP Minister. The AFP member is required to have ‘reasonable grounds’ that the order would substantially assist in preventing a terrorist act or that the person has provided training or received training from a listed terrorist organisation. The involvement of the AFP Minister is interesting because it allows a Minister to severely restrict the liberty of an individual a role usually reserved for the courts. This allows at the very least the appearance of political bias to enter the decision-making process. Section 104.2 is mainly procedural, listing the steps the AFP member should undertake to seek the order. Section 104.3 requires the AFP member to make any changes to the request for an interim control order required by the Minister.

Control Orders Balance of Probabilities

Section 104.4 allows the ‘issuing court’ to make an interim control on the civil standard of proof, being, ‘on the balance of probabilities’[19]and requires that making the order would substantially assist in preventing a terrorist act, or that the person has provided training to, or received training from a listed terrorist organisation. Section 104.4(c)(d) states”

(c) the court is satisfied on the balance of probabilities:

(i) that making the order would substantially assist in preventing a terrorist act; or

(ii) that the person has provided training to, received training from or participated in training with a listed terrorist organisation; or

(iii) that the person has engaged in a hostile activity in a foreign country; or

(iv) that the person has been convicted in Australia of an offence relating to terrorism, a terrorist organisation (within the meaning of subsection 102.1(1)) or a terrorist act (within the meaning of section 100.1); or

(v) that the person has been convicted in a foreign country of an offence that is constituted by conduct that, if engaged in in Australia, would constitute a terrorism offence (within the meaning of subsection 3(1) of the Crimes Act 1914); or

(vi) that making the order would substantially assist in preventing the provision of support for or the facilitation of a terrorist act; or

(vii) that the person has provided support for or otherwise facilitated the engagement in a hostile activity in a foreign country; and

(d) the court is satisfied on the balance of probabilities that each of the obligations, prohibitions and restrictions to be imposed on the person by the order is reasonably necessary, and reasonably appropriate and adapted, for the purpose of:

(i) protecting the public from a terrorist act; or

(ii) preventing the provision of support for or the facilitation of a terrorist act; or

(iii) preventing the provision of support for or the facilitation of the engagement in a hostile activity in a foreign country.

A control order can be regarded as similar to a sentence of home detention for a criminal offence, except that it requires a lesser standard of proof than that involved in the usual criminal sentencing process of beyond reasonable doubt, and it is imposing a sentence on a person who has not been convicted of a criminal offence.[20] Additionally, it is imposed without the requirement that there be an imminent threat of a terrorist attack.

Length of Time Under Control

Section 104.5 specifies what the issuing court must include in a control order, and as part of this process it is to specify the period during which the control order is to be in force: it allows for the order to be made for 12 months from the time the interim control order is made. Section 104.5(2) makes it very clear that the 12 months expiration ‘does not prevent the making of successive control orders in relation to the same person’. In effect, subject to the sunset provision in section 104.32 remaining beyond 2022, an individual could permanently remain the subject of a control order.

The Controls

Section 104.5(3) lists the controls that can be placed upon people. The obligations, prohibitions and restrictions are: ‘(a) a prohibition or restriction on the person being at specified areas or places; (b) a prohibition or restriction on the person leaving Australia; (c) a requirement that the person remain at specified premises between specified times each day, or on specified days, but for no more than 12 hours within any 24 hours; (d) a requirement that the person wear a tracking device; (e) a prohibition or restriction on the person communicating or associating with specified individuals; (f) a prohibition or restriction on the person accessing or using specified forms of telecommunication or other technology (including the internet); (g) a prohibition or restriction on the person possessing or using specified articles or substances; (h) a prohibition or restriction on the person carrying out specified activities (including in respect of his or her work or occupation); (i) a requirement that the person report to specified persons at specified times and places; (j) a requirement that the person allow himself or herself to be photographed; (k) a requirement that the person allow impressions of his or her fingerprints to be taken; (l) a requirement that the person participate in specified counselling or education.’

Controls Removal Presumption of Innocence and Disclosure Rights

Many of the restrictions can be placed on people who receive bail following arrest for a criminal offence. The fact that a person who is subject to a control order need not even be accused of any offence, strikes at the long held fundamental legal right that an accused is presumed innocent until a tribunal of fact determines that the prosecution has proven its case beyond reasonable doubt: Woolmington v DPP.[21] Section 104.6 provides for ‘Requesting an urgent interim control order by electronic means.’ In all cases interim control orders are issued ex parte: s104.4. That is the interests of the state as expressed by the Minister and police are the matters taken into account. This is a departure from usual practice where a person at least has a right to appear when their liberty is being determined.

Pursuant to section 104.12(1) within 48 hours, amongst other things, the person subjected to the control order needs to present their case if they are going to oppose the order being confirmed. This time restriction may put the person a considerable disadvantage, but of greater significance is the difficulty they may face in even knowing the basis for the claim that they are a future terrorist threat. Section 104.14(3) allows for information to be withheld if it is deemed to prejudice national security ‘within the meaning of the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004’; or attracts public interest immunity; or puts at ‘risk the safety of the community, law enforcement officers or intelligence officers’. Section 104.13 allows a lawyer to request a copy of the control order, but this request does not provide a basis for access to what would normally be provided in criminal cases, that is, the full factual basis upon which the prosecution is basing its case. Where full factual details are not provided it may not be possible to meet an allegation or rebut an inference drawn from facts; indeed, at its most fundamental it is not possible to prove an asserted fact to be false if you don’t know what fact is being propounded. The approach taken by the parliament to control orders has allowed for real abuse based on ‘evidence’ that may be no more than speculative nonsense. The approach also is clearly diametrically different to accepted criminal law practice. For example, in Grey v The Queen[22] the High Court of Australia held that there is an ongoing obligation on the prosecution to make full disclosure. Bar Association rules and prosecution guidelines of States and Territories also require such disclosure. Section 104.14 governs the confirming an interim control order, but it does not remedy the problem related to disclosure. Additionally, there is no real legal role for those who apply this law, any involvement being simply administrative.

Section 104.18 provides a person with the right to seek revocation or variation of a control order. This might prove very difficult to achieve if full details are not provided about why the order was made in the first place.

Penalty for Breach of Control Order

In the event that a person decides to contravene the control order, section 104.27 allows for 5 years imprisonment. This is strikingly different to the situation, which not infrequently presents, where a person breaches a bail condition and can lose the conditional liberty provided by bail until a trial is held. The person who breaches the control order, although innocent of any association with terrorism, may still go to goal for opposing the control order. Political dissent by non-compliance, even by an innocent person, is not allowed. Strikingly, and what further distinguishes a control order from the limits that can be imposed on a person in the traditional criminal justice system, is that a control order can be imposed on a person who will never be charged or tried. Control Orders can also be imposed on a person before trial and after trial if they have been acquitted, or when they have completed a sentence of imprisonment.

Children Included

Section 104.28 provides that a control order cannot be made for a person under 14 years of age and introduces special rules for young people between the ages of 14 and 17. The original legislation restricted the use of control orders to people above the age of 16 years. The change is arbitrary and there is no factual basis to support the lowering of the age. It probably reflects to view of the majority of parliamentarians that being hard on crime wins votes, in this case being hard on children is seen as a vote winner.

Sunset Provision

The original section 104.32 provided a sunset provision ending control orders in 10 years, which meant that control orders would cease to exist in December 2015. However, the Counter-Terrorism Legislation Amendment (Foreign Fighters) Act 2014 introduced a new section 104.32 which extended the sunset provision to 7 September 2018, this was later extended to 7 September 2021 and at the time of writing the Counter-Terrorism Legislation Amendment (Sunsetting Review and Other Measures) Bill 2021, passed by both houses of parliament enables an extension of the sunset provision to 7 December 2022.

Sunset provisions are included in legislation for the obvious reason that the parliament is concerned that the law is not a good one. Control orders have been given an extended lease of life and, with the increasingly harsh anti-terrorism laws being introduced, it would not be surprising if they were made a permanent feature of the Criminal Code.

The Independent National Security Legislation Monitor (INSLM) recommended the repeal of the control ordered regime established by Division 104 of the Criminal Code.[23] The recommendation has not been accepted by government. The Council of Australian Governments Review of Counter-Terrorism Legislation made a number of recommendations including one that proposed the retention of the control order regime. At the time it made its recommendation about control orders the report of the INSLM had not been completed, although the Chair of the Council of Australia Governments did have discussions with the INSLM about their respective roles.[24] The Council review recommended that the ‘control order regime should be retained with additional safeguards and protections included’.[25] Recommendations changed and added over time, what is obvious is that controls orders allow for substantial restrictions on liberty without a person being charged with a criminal offence and without any need to prove the restriction is needed, usual the usual criminal standard of proof and safeguards.

The Response of the High Court to Control Orders

The courts in Australia have shown a reluctance to do more than make limited use of statutory interpretation to limit the derogation of legal rights. There are notable exceptions where the High Court has clearly moved against the will of the government, such as the Communist Party case, or has introduced substantial change to the common law such as the Mabo case.

The leading Australian case on control orders is Thomas v Mowbray.[26] Thomas was the subject of an interim control order imposed by a Federal Magistrate on 27 August 2006. Schedule 2 of the Order gives the reasons for its imposition, that included: he trained with Al Qaeda in 2001; there was ‘good reason to believe’ he was an ‘available resource’ for Al Qaeda ‘or a related terrorist cell’; he ‘may be susceptible’ to exploitation; he ‘is attractive to aspirant extremists who will seek out his skills’; and ‘the controls . . . will protect the public’.[27] The order required Thomas to: remain at his residence between midnight and 5 am each day; report to police three times a week; submit to having his fingerprints taken; not acquire or manufacture explosives; not communicate with named individuals (50 people); not to use certain communications technologies.[28] The order was made ex parte.[29]

The special case taken to the High Court of Australia asked if Division 104 of the Commonwealth Criminal Code was contrary to Chapter III of the Constitution in that it conferred on a federal court non-judicial powers, or Division 104 was invalid because it conferred legislative power that the Commonwealth did not possess, or it was invalid because the powers were not properly referred by the States. The majority of the Court found that federal courts could exercise the powers given under Division 104, that it was not contrary to the defence or external powers of the Commonwealth, and they did not consider whether the States had properly referred their powers.

The case is of interest for the questions answered, but also because most of the judges engaged in consideration of current community expectations about how the threat of terrorism should be met, and they engaged in a process of justification based on a very few statutory and common law examples. The need to defend the community by the use of preventative laws mirrored the approach taken by a majority of federal parliamentarians.

Gleeson CJ, reflecting the opinion of the majority, said in respect of defence powers:

The power to make laws with respect to the naval and military defence of the Commonwealth and of the several States, and the control of the forces to execute and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth, is not limited to defence against aggression from a foreign nation; it is not limited to external threats; it is not confined to waging war in a conventional sense of combat between forces of nations; and it is not limited to protection of bodies politic as distinct from the public, or sections of the public.[30]

When considering the preventative nature of the law and how courts could apply such laws Gleeson CJ used the example of Fardon v Attorney-General (Qld),[31]which involved State legislation that allowed the Supreme Court of Queensland to keep people in custody who had completed their sentences, to lend support to the proposition that preventative laws are allowable. Gleeson CJ also said the examples of ‘executive detention pursuant to statutory authority include quarantine, and detention under health legislation’.[32] He specifically excluded consideration of procedural fairness from his considerations, stating:

We are not concerned in this case with particular issues as to procedural fairness that could arise where, for example, particular information is not made available to the subject of a control order or his or her lawyers. Issues of that kind, if they arise, will be decided in the light of the facts and circumstances of individual cases. We are here concerned with a general challenge to the validity of Div 104. That challenge should fail.[33]

Perhaps the questions could have covered the obvious examples contained within Division 104 of the Criminal Code that do not allow for such fairness. In Re Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs; Ex parte Lam,[34] four years before, Gleeson CJ referred to the law of procedural fairness as involving a process designed to avoid practical injustice.[35] In this regard legal representation is clearly an issue, as is the provision of all relevant facts, something that can be absent for a person confronting a control order. However, in Thomas v Mowbray[36] he was confining himself to the challenge to the validity of Division 104 as a constitutional issue. It appears that Gleeson CJ was leaving open the possibility of a challenge to a control order based on procedural fairness.

Kirby J, in the minority, stated:

In my view Div 104, as enacted, lacks an established source in federal constitutional power. It also breaches the requirements of Ch III of the Constitution governing the judicial power of the Commonwealth. Division 104 is therefore invalid.[37]

He was concerned, when dealing with the referring powers of States, to stress the care that needs to be taken before the presumption in favour of common law rights can be overcome.

Australian legislation is not ordinarily taken to invade fundamental common law rights or to contravene the international law of human rights, absent a clear indication that this is the relevant legislative purpose. . . Div 104 of the Code directly encroaches upon rights and freedoms belonging to all people both by the common law of Australia and under international law.[38]

Kirby J noted and regretted the court’s break with tradition in finding the legislation constitutionally valid. He stated:

Whereas, until now, Australians, including in this Court, have generally accepted the foresight, prudence and wisdom of this Court, and of Dixon J in particular, in the Communist Party Case (and in other constitutional decisions of the same era), they will look back with regret and embarrassment at this decision when similar qualities of constitutional wisdom were demanded but were not forthcoming.

In the face of contemporary dangers from terrorism, it is essential that this Court should insist on the steady observance of settled constitutional principles. It should demand adherence to the established rules governing the validity of federal laws and the deployment of federal courts in applying such laws. It should reject legal and constitutional exceptionalism. Unless this Court does so, it abdicates the vital role assigned to it by the Constitution and expected of it by the people. That truly would deliver to terrorists successes that their own acts could never secure in Australia.[39]

Hayne J, in the minority, found that federal courts did not have the power to make or confirm an interim control order. He found that Division 104 provided no legal standards that a court could apply.[40] Callinan J was a supporter of the legislation, Heydon J’s decision was brief and agreed with Gleeson, Gummow and Crennan JJ.

The ultimate role of the courts in determining the full extent to which the terrorist laws derogate fundamental legal principles remains moot. Recent history, however, suggests that the High Court of Australia is more likely to support parliamentary legislative power than fundamental legal rights when confronted by a determined government, if the most relevant recent case Thomas v Mowbray is any guide.

Preventative Detention Orders

The Anti-Terrorism Act (No2) 2005 introduced Preventative Detention Orders found in Division 105 of the Criminal Code. Section 105.1 provides the ‘object’ of such orders. It states: ‘The object of this Division is to allow a person to be taken into custody and detained for a short period of time in order to: (a) prevent an imminent terrorist act occurring; or (b) preserve evidence of, or relating to, a recent terrorist act’. Section 105.5 stops a preventative detention order from being made if the person is under 16 years of age. Section 105.5A allows for interpreters for those with inadequate knowledge of English or who have a disability.

Issuing Authority for Preventative Detention Orders

Section 105.2 allows the Attorney-General to appoint a person who is an ‘issuing authority’ for continued preventative detention orders. The issuing authority is required to be a judge or former judge, or President or Deputy President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, or a legal practitioner who has been enrolled for at least 5 years. If the person is a serving judge, magistrate or member he or she is required to act in a personal capacity. The requirement for the issuing authority to act in a personal capacity recognises that courts cannot be issued with non-judicial powers or functions.[41] What is clear, when the sections are read as a whole, is that the role performed by an issuing authority is administrative, and scope for the exercise of any discretion to reject an application is extremely limited.

Section 105.4(4) allows an AFP member to apply for a preventative detention order if the member pursuant to subsection (a) ‘suspects, on reasonable grounds, that the subject: (i) will engage in a terrorist act; or (ii) possesses a thing that is connected with the preparation for, or the engagement of a person in, a terrorist act; or (iii) has done an act in preparation for, or planning, a terrorist act’: subsection (b) allows the issuing authority to make the order on the same grounds. The terrorist act must be imminent and expected to occur within 14 days: subsection (5). If the terrorist act has occurred within 28 days and the person needs to be detained in order to preserve evidence, an order can be issued: subsection (6). The grounds for reasonable suspicion are phrased very broadly, so it is unlikely that an application would be rejected.

Section 105.42 is internally inconsistent in that it restricts questioning of the person in custody to those matters involving welfare and safety but allows questioning if: ‘Note 1: This subsection will not apply to the person if the person is released from detention under the order (even though the order may still be in force in relation to the person)’. The scope for abuse is obvious. The restriction on questioning applies to police, ASIO employees and affiliates, except if they are questioning for safety issues and then it is to be recorded except where ‘not practicable because of the seriousness and urgency of the circumstances in which the questioning occurs’: s 105.42(5)(b). If the desire is simply to question and urgent circumstances cannot be found, the police can obtain a questioning a warrant under the Australian Security Intelligence Act 1979.

Initial Preventative Detention Order

Section 105.7 allows for an initial preventative detention order, and under section 101.1(1) a senior AFP officer is an issuing authority for the purpose of an initial preventative detention order. The use of a senior AFP member as an issuing authority simply means that the police can detain a person for a set period, without charge and without reference to any type of judicial authority. Subsection (2A) allows the AFP member to avoid disclosing, in a summary to the issuing authority, any grounds for wanting the order that are likely to prejudice national security as provided for in the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004. This provision exists whenever an order is being sought. In the first instance this may provide limited information to another police officer and if the order is continued to someone in a quasi-judicial role. Section 105.8(5) allows for an initial detention order to not exceed 24 hours. Section 105.9(2) allows for the initial preventative detention order to cease having effect at the end of 48 hours, if the person has been taken into custody in that time.

Extension of Time Initial Preventative Order

Section 105.10 allows for the extension of an initial preventative order for 24 hours. Section 105.11 allows for an application for a continued preventative detention order, and subsection (5) allows for another 24 hours.

Continued Preventative Detention Order

Section 105.12 allows a judge, AAT member or retired judge to make continued preventative detention order on application by an AFP member if: ‘(a) an initial preventative detention order is in force in relation to the person; and (b) the person has been taken into custody under the order (whether or not the person is being detained under the order).’

Section 105.14 allows for an extension of a continued preventive detention order, however, subsection (6) states: ‘The period as extended, or further extended, must end no later than 48 hours after the person is first taken into custody under the initial preventative detention order’. The total period in custody, therefore, seems to be 48 hours. State legislation, however, allows for detention up to 14 days.[42] For example, subsections 26K(1)(2) of the Terrorism (Police Powers) Act 2002 (NSW) states:

26K Maximum period of detention and multiple preventative detention orders

(1) In this section—

related order, in relation to a person, means an interim preventative detention order, another preventative detention order or an order under a corresponding law that is made against the person.

(2) The maximum period for which a person may be detained under a preventative detention order (other than an interim order) is 14 days. That maximum period is reduced by any period of actual detention under a related order against the person in relation to the same terrorist act.

Prohibited Contact Order

Section 105.14A and subsequent sections allow for a prohibited contact order. Section 105.34 restricts contact with other people while the person is in preventative detention. Section 105.35 requires the agreement of the police officer detaining the person for contact to be made with anyone else, including family members, and if permission is given subsection (1)(f) limits the contact to ‘solely for the purposes of letting the person contacted know that the person being detained is safe but is not able to be contacted for the time being’. Section 105.36 allows the person to contact the Ombudsman, and section 105.37 allows contact with a lawyer for limited purposes. Section 105.38 allows contact only if it can be effectively monitored. The limited contact requirement is bizarre, and in the case of terrorist belonging to a group their sudden absence would probably alert the others to the involvement of police.

Limitations of Appeal

Preventative detention orders cannot be appealed at the relevant time when a person is in custody. Section 105.51(2) excludes the possibility and thus breaches a fundamental legal right to appeal. There seems to be some attempt to cover this breach by allowing an appeal to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, pursuant to s105.51(7), to seek a decision set aside the order thus making it void. Compensation for the detention can be paid pursuant to s105.51(8). The possibility of a decision being made in favour of a person subjected to an order must be significantly limited because of the restricted access to the evidence used to invoke the order. Apart from the fact that a person can be taken into custody and held for up to 14 days without the right of appeal, there is no requirement that the person be charged with an offence or even that there be sufficient evidence to allow the person to be charged.

Preventative Detention Order Secrecy Provisions

Section 105.41 of the Code governs disclosure offences. Section 105.41(1) makes it an offence for a person detained under a preventative detention order to disclose to another person the fact that a preventative detention order has been made, or the fact of detention, or the period of detention while subject to the order. Section 105.41(2) makes it an offence for the lawyer of the person subject to a preventative detention order to disclose to another person the fact that a preventative detention order has been made, or the fact that the detainee is being detained, or the period for which the detainee is being detained, or any information that the detainee gives the lawyer in the course of the contact. These restrictions apply for the period the order is in force, and do not apply to proceedings in the federal court, a complaint to the Commonwealth Ombudsman or to the federal police. Section 105.41(3) has similar restrictions on a parent/guardian where the person subject to an order is under 18 years of age or incapable of managing their own affairs (further qualifications and restrictions can be found in subsections (4) and (4A)). Section 105.41(5) creates an offence for an interpreter to disclose information. Section 105.41(6) makes it an offence for a person who has received information from passing it on. Section 105.41(7) makes it an offence for a police officer or an interpreter who monitors communication between a detained person and a lawyer to disclose the information to another person. Section 105.41 offences carry a penalty of 5 years imprisonment. There are no similar restrictive provisions in the traditional criminal laws of Australia.

Sunset Provision for Prevention Detention and Contact Orders

Section 105.53 provides for a sunset provision similar to control orders. It was also extended from concluding in 2015 to conclude on 7 September 2018 and has been subsequently extended to 7 December 2022. In 2012, before this extension, the Independent National Security Legislation Monitor recommended the repeal of the preventative detention regime established by Division 105 of the Criminal Code.[43] The main reason given for this recommendation was that the powers of arrest, charging, detention and trial allowed for in the tradition criminal justice system would be more effective in preventing a terrorist act while maintaining due process and the right to a fair trial.[44]

The Council of Australian Governments Review of Counter-Terrorism Legislation, by a majority, also recommended the repeal of the Division.[45] The response of the government to this recommendation can best be seen by the fact that it extended the sunset provision from 2015 to 7 September 2018 and subsequently. It also introduced the Independent National Security Legislation Monitor Repeal Bill 2014 designed to abolish the position of Monitor, presumably because the government did not like some of the recommendations it was receiving. In a submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs inquiry concerning the Bill, the Law Council of Australia noted with disappointment the lack of response by the government to the Monitor’s recommendations.[46] The Law Council also supported the retention of the Monitor.[47] Media reports indicate that the Labor Party and Greens opposed the repeal Bill in the Senate.[48] On 17 July 2014, the bill was discharged from the House of Representatives Notice Paper. The Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs has resolved that it would not pursue its inquiry.[49]

Foreign Fighters

The Counter-Terrorism Legislation Amendment (Foreign Fighters) Act 2014 repealed the Crimes (Foreign Incursions and Recruitment) Act 1978 and introduced a range of amendments to the Crimes Act 1914, the Criminal Code 1995, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979 and seventeen other statutes. All the amendments were designed to increase restrictions on individuals who may be engaged in some form of terrorist activity. The legislation was introduced on 24 September 2014 and finally passed both Houses of Parliament on 30 October 2014. The speed with which this legislation was passed and the superficial consideration given to it by Labor and Liberal parliamentarians is considered in Chapter 7.

The Counter-Terrorism Legislation Amendment (Foreign Fighters) Act 2014 shows a further growth in punitive legislation that restricts the right to fair trial. The Act amended Criminal Code (some of the amendments have been referred to earlier) and introduced Part 5.5 ‘Foreign incursions and recruitments’. Apart from dramatically increasing sentences for offences that previously existed under the repealed Act, it introduced absolute liability offences which make it significantly easier for the prosecution to prove that a criminal offence has been committed.

Section 119.1 allows for life imprisonment for incursions into foreign countries with the intention of engaging in hostile activities, and the same term of imprisonment for engaging in a hostile activity in a foreign country. Of course state approved invasions of foreign countries are not included.

Section 119.2 makes it an absolute liability offence to enter or remain in an area declared by the Minister for Foreign Affairs (section 119.3) in a foreign country if the person ‘(i) is an Australian citizen; or (ii) is a resident of Australia; or (iii) is a holder under the Migration Act 1958 of a visa; or (iv) has voluntarily put himself or herself under the protection of Australia’. The penalty is 10 years imprisonment. This is a draconian section, and amongst other things, has the potential to stop a person trying to protect their family in their country of origin.

Apart from the power given to a single politician to declare the entry of a particular area of a foreign land a prohibited area, overseen by a weak parliamentary committee, the creation of absolute liability offences means that there is no requirement that the person intended to enter the area before a conviction can be recorded and there is no defence of mistake. Power of this type in the hands of politically driven individuals, coupled with making non-intentional acts criminal, move Australia closer to countries where the rule of law is based on tyranny and individuals are powerless against the controllers of the state.

Terrorism and the Crimes Act 1914

The Crimes Act 1914 also contains significant anti-terrorism laws that remove or reduce pre-existing legal rights. Part 1AA, Division 3A of the Act contains powers to stop, question and search persons in relation to terrorist acts. Division 4B gives power to obtain information and documents in terrorism investigations. Part 1AE provides for video link evidence in proceedings for terrorism offences. Part 1A, section 15AA provides that bail be given only in exceptional circumstances for terrorist offences.

The requirement for exceptional circumstances before bail is granted is a significant change to the common law where there is a presumption in favour of bail. The exceptional circumstances requirement imposes on the judiciary the requirement that they presume the accused to be a significant risk and effectively eliminates consideration of the presumption of innocence. These additions to the existing laws are less invasive of rights than those contained in other statutes.

Metadata Laws

Metadata laws passed on 26 March 2015 are contained in the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Amendment (Data Retention) Act 2014. It amended the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 to require a service provider to keep data. Sections 187A and 187C of the amended Act requires data to be kept by a service provider for a minimum period of two years. Section 187AA of the Act specifies in a Table that can be changed by legislative instrument, amongst other things: ‘the date and time (including the time zone) of the following relating to the communication (with sufficient accuracy to identify the communication): (a) the start of the communication; (b) the end of the communication; (c) the connection to the relevant service; (d) the disconnection from the relevant service’.

Section 187A(4) states: ‘This section does not require a service provider to keep, or cause to be kept: (a) information that is the contents or substance of a communication; or Note: This paragraph puts beyond doubt that service providers are not required to keep information about telecommunications content’.

An amendment designed to gain bipartisan support in order to pass the bill included a concession to journalists that provides very limited protection if the communication was with a source. Section 180H of the Act requires a warrant to access the communication of journalist. The protections are what can reasonably be described as a veneer.

There was a chorus of opposition to the new laws, mainly from journalists. For example, Paul Murphy, the Chief Executive Officer of the Media, Entertainment, and Arts Alliance, stated ‘Accessing metadata to hunt down journalists’ sources, regardless of the procedures used, threatens press freedom and democracy’.[50]

Apart from increasing the reach of the surveillance state, the laws are arguably in breach of the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights,[51] Part III, Article 17(1) states: ‘No one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his honour and reputation’. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights contains the same wording with the exception of ‘unlawful’.

The justification for the laws is largely limited to the generalities as expressed by Attorney-General, George Brandis in terms of the need to fight against terrorism and paedophilia. The use of paedophiles to promote the laws is presumably to suggest that anyone who does not support the laws does not want to catch such hated criminals.[52]

In 2014, the European Court of Justice issued a directive that the retention of mass data was invalid. The European Parliament had issued Directive 2006/24/EC on the retention of data generated or processed in connection with the provision of publicly available electronic communications services or of public communications networks. The High Court of Ireland and the Constitutional Court of Austria had asked the Court of Justice to examine the validity of the directive. The Court emphasised the fundamental right to a private life.[53]

The effectiveness of meta-data laws, as with other specifically focused anti-terrorism laws, is very doubtful. France had metadata laws in place at the time of the Charlie Hebdo shootings in Paris in January 2015, but they did not prevent that tragedy, and examples of the effectiveness of the laws are not provided by their promoters.

National Security Secrecy

The National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004[54] is legislation that falls within the anti-terrorist category; however, it has much broader application and can be applied wherever a national security issue is raised in a federal criminal trial. It is an extraordinary piece of legislation that claims to be designed to protect national security but strikes at the very fundamentals of an accused’s right to a fair trial. It allows the prosecution to proceed without providing full disclosure, requires the defence to disclose information they otherwise would not, allows the court to exclude the accused and their counsel from a hearing where it relates to a national security issue, allows admissibility issues about national security to be heard in a closed court, provides a definition of ‘national security’ that is so broad that it allows state agencies to hide their own illegal abuses of the law from scrutiny, and introduces severe penalties for non-compliance with the Act. As with other significant anti-terrorist legislation, it emphasises procedure over substance, gives significant powers to the Attorney-General, and provides extremely broad definitions.

The object of the Act is stated in section 3 is to ‘prevent the disclosure of information in federal criminal proceedings where the disclosure is likely to prejudice national security, except to the extent that preventing the disclosure would seriously interfere with the administration of justice’. A court is required to have regard to the object when performing its functions.

The proviso ‘except to the extent that preventing the disclosure would interfere with the administration of justice’ is neat, but when other sections of the Act are applied it becomes virtually meaningless.

Section 6 of the Act stipulates that it applies to all federal criminal proceedings where a prosecutor gives notice. Section 13(2) clarifies any doubt about the extent of criminal proceedings and therefore the coverage of the Act by including: ‘a bail proceeding; a committal proceeding; the discovery, exchange, production, inspection or disclosure of intended evidence, documents and reports of persons intended to be called by a party to give evidence; a sentencing proceeding; an appeal proceeding; a proceeding with respect to any matter in which a person seeks a writ of mandamus or prohibition or an injunction against an officer or officers of the Commonwealth (within the meaning of subsection 39B(1B) of the Judiciary Act 1903) in relation to: (i) a decision to prosecute a person for one or more offences against a law of the Commonwealth; or (ii) a related criminal justice process decision (within the meaning of subsection 39B(3) of that Act); and (g) any other pre‑trial, interlocutory or post‑trial proceeding prescribed by regulations’.

The Act applies to proceedings where disclosure is likely to prejudice ‘national security’ and includes an attempt made to define ‘national security’. This attempt is made in Division 2, sections 8, 9, 10, and 11. Julian Burnside QC makes the point that the definition is so wide that national security could be affected if evidence was brought showing:

- that a CIA operative extracted a confession by use of torture;

- operational details of the CIA, Interpol, the FBI, the Australian Federal Police, the Egyptian Police, the American authorities at Guantanamo Bay, etc; and

- the use of torture or other inhumane interrogation techniques by any law enforcement agency.[55]

The scope for abuse is substantial, and evident from reports into abuses of prisoners in Abu Ghraib. Interrogation techniques used in Guantanamo, Afghanistan and Iraq involved stress positions, isolation for up to 30 days, exploiting fear of dogs, removal of clothing, sleep and light deprivation.[56] Those torture techniques were seemingly approved and would probably be excluded from disclosure in an applicable case in Australia if the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004 was invoked. The use of torture by the United States in Guantanamo, Afghanistan and Iraq is not an aberration that can be dismissed as happening in unique circumstances confined to a short period of time.[57] There is substantial evidence that the United States has a disgraceful history of funding murderous regimes that engaged in torture, and of using the CIA to fund others to torture on their behalf.[58]

Section 21 provides for pre-trial conferences where the prosecutor has issues about disclosure. Section 22 allows arrangements to be made about disclosure between the prosecutor and the defence. Section 23 governs the storage, handling and disposal of information disclosed in court. Section 24 requires the prosecution and defence to advise the Attorney-General if they believe they will disclose information that relates to or affects national security. Considering the very broad definition of national security contained in the Act, the application of the section could keep the lawyers and the Attorney-General very busy. This section imposes on the defence a disclosure requirement that is not usual in a criminal trial, where defence disclosures prior to the presentation of the defence case are very limited; and subject to being waived by the trial judge in the interests of justice. The section also has the potential for restricting cross examination, and otherwise crippling a trial through continual adjournments whilst the decision of the Attorney-General is sought. Section 25 relates to witnesses not disclosing evidence that relates to or may affect national security. It has similar procedural and fairness problems as section 24.

Section 26 allows the Attorney-General to give a non-disclosure certificate identifying for the potential discloser what they can not disclose. If a non-disclosure certificate is given pursuant to section 27 and 28, the court must hold a hearing to determine what order to make pursuant to section 31. As part of process the court must have a closed hearing pursuant to section 29.

The defendant and his lawyer can be excluded from the hearing (section 29(3) if they do not have appropriate security clearances. It would probably be very unlikely that a criminal defendant would be given a security clearance. Moreover, the basis for not granting a security clearance is not open to meaningful review.

The Attorney-General can intervene on behalf of the Commonwealth. Pursuant to section 31 the court can decide whether to admit the contested information or witness evidence or not, however, when making this decision subsections (7) and (8) are relevant. Subsections 31(7)(8) state:

Factors to be considered by court

(7) The Court must, in deciding what order to make under this section, consider the following matters:

(a) whether, having regard to the Attorney-General’s certificate, there would be a risk of prejudice to national security if:

(i) where the certificate was given under subsection 26(2) or (3)—the information were disclosed in contravention of the certificate; or

(ii) where the certificate was given under subsection 28(2)—the witness were called;

(b) whether any such order would have a substantial adverse effect on the defendant’s right to receive a fair hearing, including in particular on the conduct of his or her defence;

(c) any other matter the court considers relevant.

(8) In making its decision, the Court must give greatest weight to the matter mentioned in paragraph (7)(a).

Subsection (8) in effect requires the court to give greatest weight to the Attorney-General’s certificate which is designed to exclude information or witness evidence; and without having fully tested the basis for the granting of the certificate. This factor alone is sufficient to say that the proviso in section 3 that states, ‘except to the extent that preventing the disclosure would interfere with the administration of justice’ is neat but virtually meaningless.

Ian Barker QC described the impact of the Act as effectively taking from the court and giving to the executive the power to determine whether a claim for public interest immunity has been made out.[59] Former High Court Justice Michael McHugh added his voice to those who found the legislation repugnant, stating: ‘It weights the exercise of the discretion in favour of the Attorney-General and in a practical sense directs the outcome of the closed hearing. How can a court make an order in favour of a fair trial when in exercising its discretion, it must give the issue of fair trial less weight than the Attorney-General’s certificate?’[60] Spencer Zifcak notes that non-disclosure allowed by section 31 of the Act gives paramountcy to broadly defined national security over the interests of justice, and concludes that if the balancing exercise previously found necessary by the High Court is not followed then ‘from the human rights perspective, that would be a most damaging outcome’.[61] The fact that non-disclosure could result in a fair trial being given less weight than it should, means that if it resulted in a conviction it probably was not a fair trial. The Act makes the unfair result legally acceptable, thus placing such cases squarely in a parallel legal system where the various participants who apply the law have a fractured relationship.

Conclusion

The introduction of the control orders and preventative detention orders into the Criminal Code 1995 has removed the necessity for the right to liberty to be preferred over detention. There is also no need to apply the requirements of a fair trial, such as disclosure and appropriate legal representation, when making orders or imposing preventative detention. There is also no requirement that a person actually be charged with a criminal offence for an order or preventative detention to be imposed. In the event that a person is eventually charged and goes to trial, the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004 can result in the trial being unfair. The definition of terrorism in the Code allows for people to be charged with a terrorism offence who should be dealt with through the traditional criminal justice system where fundamental legal rights play a significant part. The Code also allows for Ministerial outlawing of organisations and imposes severe appeal restrictions. It introduces strict liability offences, associating with a listed organisation and reverses the onus of proof for an accused. Additionally, the Code introduces the offence of planning a terrorist act that is so encompassing that it could result in a conviction on ambiguous evidence and is so broad it verges on making it a crime to have juvenile thoughts about engaging in destructive acts. Apart from the planning and association offences, the substantive terrorism offences contained in the Code are in fact comprehensively covered by pre-existing criminal laws.

References

[1] Andrew Lynch, Nicola McGarrity and George Williams, Inside Australia’s Anti-Terrorism Laws and Trials (NewSouth Publishing, 2015) 3.

[2] Apart from the specific changes detailed in this chapter the Security Legislation Amendment (Terrorism) Act 2002 also made changes to the offence of treason.

[3] Hyam v DPP [1975] 2 All ER 41 highlights distinction between intention and motivation. The section mixes the distinction.

[4] Introduced through the Security Legislation Amendment (Terrorism) Act 2002 and the Anti-Terrorism Act 2005.

[5] [2006] NSWSC 691.

[6] Ibid 53.

[7] Ibid 54.

[8] Faheem Khalid Lodhi v Regina [2006] NSWCCA 121; (2006) 199 FLR 303.

[9] Ibid [1].

[10] Ibid [2].

[11] Ibid [3].

[12] Ibid [4].

[13] Ibid [66].

[14] In 2015 there were 20 listed terrorist organisations: see Appendix B.

[15] Wiseman v Borneman [1971] AC 297; Kioa v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs (1985) 62 ALR 321.

[16] Roger Douglas, ‘Proscribing terrorist organisations: Legislation and practice in five English-speaking democracies’ (2008) 32 Crim LJ 99.

[17] Law Council of Australia, ‘A consolidation of the Law Council of Australia’s advocacy in relation to Australia’s anti-terrorism measures’, Anti-Terrorism Reform Project, October 2013, 74.

[18] The Anti-Terrorism Act (No. 2) 2005 also introduced updated sedition laws. Consideration of the sedition laws does not form part of this work, although they can be viewed as part of the ongoing package of anti-terrorism laws.