Colin Campbell Eadie Ross (1892-1922)

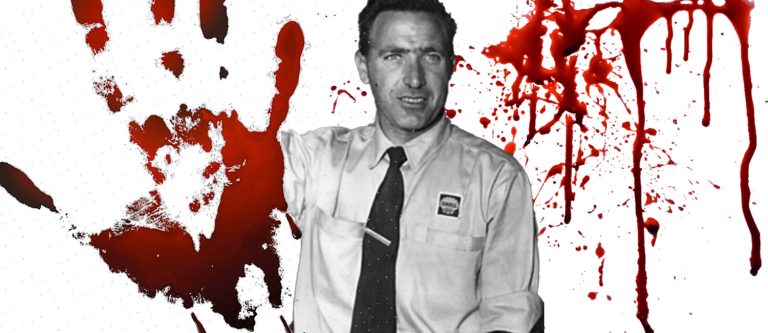

Colin Ross’s Background

Colin Ross was born in Melbourne, Australia and had a difficult life. With four siblings, his father died when he was just eight years old, leaving he and his siblings to be cared for by his mother. This would have been challenging for the family and as a result, none were well educated, and each had to leave school as soon as possible to begin the process of earning an income to contribute to the family. Colin was already working by the age of 11 and over his first few years worked as a labourer and later as a wardsman in an army hospital.

By 1920, Colin was 28 years old and he, his brother and his mother took over the management of the Donnybrook Hotel[1]. At about this time he formed a relationship with a woman, Lily Brown, and after he asked to marry, she turned him down and Colin became angry. He even produced a revolver and then stalked her. She involved the police, and he was arrested and charged. The court proceedings led to him being convicted for carrying a firearm and using threatening words. He received a sentence of 14 days, but this was suspended.

A year later, the family returned to Melbourne where Colin and two brothers purchased a wine shop, called ‘The Australian Wine Saloon’. In this setting, the brothers were prepared to serve people they should not have and the established developed a negative reputation.[2] This worsened when the police investigated a shooting that occurred within the bathroom and the police determined that the assailant was working for Colin Ross in an effort to rob the patron who was already very drunk. The matter went to court, but Colin was acquitted of armed robbery although the assailant served six months for his involvement.

The Murder

On December 30, 1921, a 12-year-old girl, Alma Tirtschke, was sent to the shop by her grandmother on an errand. The journey should have taken her from Swanston Street in Melbourne to Collins Street, which was usually no more than 15 minutes, but she did not return and the next morning her body was found in Gun Alley which is a laneway of Little Collins Street. She had been raped and strangled.

The Investigation

The investigation was characterised by its lack of an immediate arrest and the newspapers were very critical of the police. Pressure mounted for them to get a result.[3]

A large reward was offered for information and the police had established that she was outside the saloon managed by Colin Ross and that he reported that he had seen her. The police developed a keen interest in his activity, particularly given that he was well known to them because of his recent interaction with the police and courts. It was not long before they had concluded that he had killed the girl and he was arrested on January 12, 1922.

The Trial & Following Representations

Ross always claimed he was innocent; from the day he was arrested up till the time he was executed. However, the trial went against him. The public was extremely interested in the case and the newspapers were constantly publishing material that implied he was guilty even before trial.

During the trial, witnesses claimed that he had confessed his guilt to them. These witnesses included another prisoner who had previously been convicted for perjury, a prostitute, and a fortune teller. ‘Forensic’ evidence in the form of a hair sample was examined by a state government analyst but this person had little experience in what was itself a new field of science. His evidence was that a hair found in Colin Ross’s house was different in colour and diameter to that of the murdered Alma yet managed to provide a conclusion that the hair found in Ross’s house was from the deceased. Ross’s Barrister sought to have a further examination by someone more experienced, but the judge refused and allowed the earlier forensic opinion to stand.

The jury found Ross guilty, and he was sentenced to death by hanging and the newspapers and public were excited about the result. Brennan’s own legal representatives were convinced of his innocence however and sought leave to appeal to the Privy Council, but this was denied[4], and Colin Ross was executed by hanging on April 24, 1922.

Ross’s Barrister, Thomas Brennan never accepted the court’s ruling and, in the years, following Ross’s execution he wrote a book, ‘The Gun Alley Tragedy[5]’, which put the case for Ross’s innocence. The book was helpful in that he managed to gain supporters but when he tried to convince the Victorian government to re-open the case on the basis of his work and the newfound support, this was not enough.

The Renewal of Interest

Naturally, with Ross dead and the efforts of Brennan not achieving their goal, interest in the case eventually died off until more than seventy years later when a retired schoolteacher, Kevin Morgan became interested in the case and began researching the case. Morgan’s research led to the discovery of information that had been kept from the court at the time of the trial and surely would have led to Ross being found not guilty.

- One discovery was the fact that there were reliable witnesses who placed Ross in his own saloon at the time Alma Tirtschke was murdered but this information was not presented to the court.

- Another discovery was a witness who reported hearing screams coming from another building, presumably the time the murder was occurring which was a time the witnesses were able to place Ross in his saloon.

- The prisoner who provided damning testimony of Ross’s alleged confession led to the prisoner’s sentence being significantly reduced.

- The prostitute and fortune teller who provided evidence against Ross received the reward money together and they shared what today would be the equivalent of $110,000, a significant sum of money.

A couple of years after starting his investigation, Morgan found a file containing the original hair samples. After a long struggle, the samples were submitted for DNA testing in 1998 with the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine and the AFP and it was confirmed that the hairs were not from the same person[6]. This disproved the only ‘forensic evidence’ of the trial, though this evidence was used to provide convincing proof at trial.

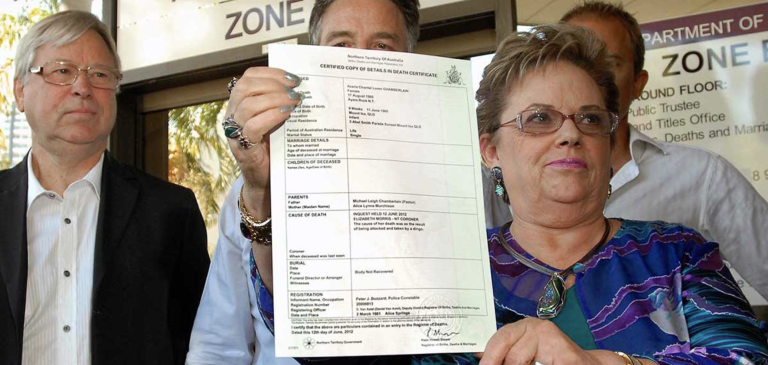

The Pardon

In 2005 the family of Colin Ross and Alma Tirtschke submitted a petition of mercy. One year later, the attorney general forwarded the petition to the chief justice asking for the petition to be considered. A further year on, the Supreme Court considered the matter and found unanimously that the case did represent a miscarriage of justice[7]. A pardon was granted on May 27, 2008. However, this is not the same has having the conviction quashed, Ross is still guilty but has been pardoned.

The Problems Are Not Just a Product of Being a Century Ago

Alma Tirtschke was murdered almost 100 years ago and a man, Colin Ross was executed for her murder less than five months later. In 2021, the speed and finality of a conviction would not occur in Australia; nothing happens that quickly and the last execution in Australia occurred in 1967. However, this is where the differences stop, the things that saw Ross convicted can and do still occur today. In 2004 the Department of Justice published a report seeking to identify strategies to prevent miscarriages of justice[8]. The recommendations of the report were largely pertinent to the case of Colin Ross, the following headings refer to the findings of the report, the paragraph shows how the broad finding relates to Colin Ross.

Tunnel Vision

The development of tunnel vision in the initial investigation and the subsequent trial and appeals process introduces a significant danger of the players developing and acting on tunnel vision. Tunnel vision can come from a variety of sources including media pressure, public opinion, preconceived notions of the accused’s character and political will.

The case of Ross demonstrates several of these factors:

- The murder sparked intense public interest;

- The newspapers reported it in an explosive fashion designed to further arouse public interest and sell newspapers;

- The police homed in on Ross largely as a result of their prior dealings with him;

- Once convicted, the judiciary denied a process of appeal to re-consider the case.

False Confessions

The report identifies false confessions as a potential problem. However, in the case of Ross, there was no false confession – Ross declared his innocence from the day he was first accused and did not believe he would be convicted because he was sure that the truth would be found. Of course, this was not the case, and he was convicted, but Ross maintained his innocence throughout and never confessed to the crime.

Eyewitness Identification

The report of the Department of Justice makes recommendations about the way in which eyewitness identification should be secured. The fallibility of eyewitness identification in different circumstances is identified as a serious problem. In Ross, the police sought eyewitness statements from a variety of people, and the most notable element of this was the fact that the eyewitness statements were largely inconsistent. Of note, Morgan’s investigation revealed that while eyewitnesses were presented to court to support the prosecution case, there were other witnesses who were not presented because they did not support the prosecution case. This demonstrates two issues: first, different supposed eyewitnesses reported different accounts, and second, the prosecution used a tunnel vision approach and only considered information supportive of their views.

In Custody Informers

The report made recommendations regarding the use of in-custody informers, particularly noting the dangers of dubious reliability when using in-custody informers. In the Ross case, an in-custody informer who alleged that Ross had confessed to him while in prison was an important piece of the prosecutions case. The use of this ‘evidence’ is made worse when the fact that the informer received benefits in return for the testimony.

Forensic Evidence and Expert Testimony

Forensic evidence is an important aspect of many trials in today’s world. However, its misuse can lead to incorrect conclusions and the impact of incorrect, inaccurate, or scientifically unsupported forensic conclusions cannot be overstated. In 1922, the use of forensic evidence was in its infancy and the scientific basis for its use was still developing. However, in Ross, the government scientist was inexperienced, and it is notable that the reported observations are not consistent with the conclusions presented to the court. The scientist could have been negligent or incompetent in providing the final opinion but could equally have been influenced passively by wanting to provide the answer expected of him by the prosecution or even been pressured in some other way. Either way, the mismatch of the observations and the opinion should have led to a different conclusion at the time. The reality of the error was made clear when the hairs were examined in modern forensic laboratories.

Closing Remarks

The case of Colin Ross is one hundred years old and only recently was proven to have been a miscarriage of justice. However, not only was Ross the subject of injustice, but the miscarriage also ensured that Alma Tirtschke or her family did not receive justice either. A first reading of this case might lead one to think, well that was a long time ago, it could not happen like that now. Tragically though, it does.

Not only do miscarriages of justice still occur, but miscarriages often occur as a result of exactly the same failures: tunnel vision, improper consideration of eyewitness evidence, a failure of forensic evidence and the use of informers who are likely to be unreliable for various reasons, especially when they gain from their involvement. It is incumbent on everyone involved in the justice system to ensure that their role is take seriously in the spirit of justice and not in supporting their own views, ego, or career development.

[1] Kevin Morgan, Gun Alley: Murder, Lies and Failure of Justice (Simon & Schuster, 2005) 111.

[2] Ibid 113.

[3] Australian Dictionary of Biography 2008) ‘Ross, Colin Campbell Eadie (1892–1922)’.

[4] Ross V the King [1922] HCA 4.

[5] Thomas C Brennan, The Gun Alley Tragedy: Record of the Trial of Colin Campbell Ross (Project Gutenberg, 1922).

[6] James Moore, Murder by Numbers – Fascinating Figures Behind the World’s Worst Crimes (History Press, 2018) 68.

[7] Re Colin Campbell Ross [2007] VSC 572.

[8] FPT Heads of Presecutions Committee Working Group, ‘Report on the Prevention of Miscarriages of Justice’, Department of Justice Canada, September 2004).